After five tumultuous years, Police Commissioner Michael Matthews passes the torch

Having already spent more than 30 years in law enforcement agencies in the United Kingdom and in Cyprus, a Mediterranean island in the British Commonwealth, Mr. Matthews thought he was ready to retire.

After some more consideration, his mind started to change.

“The opportunity to come to such a beautiful location, and to do a really challenging and interesting and fascinating role here, just became too much to respond to,” he said during a Monday interview.

Mr. Matthews’ arrival in the VI in 2016 came shortly before a calamitous period in the territory’s history.

During his five years as commissioner, he led the police force through the most devastating hurricane in recent memory, the subsequent rebuilding, and a pandemic.

These unforeseen events disrupted many of the reforms Mr. Matthews initially sought to make early in his tenure.

The devastation of the 2017 hurricanes hobbled his ambitions of modernising the police force, and travel restrictions that have helped keep the coronavirus at bay in the VI have led to a pile-up of drug stashes that police believe have fueled a recent surge of violence.

Mr. Matthews’ departure also comes during what could be a transformative period for the territory and the police force.

After police in November seized a record-setting 2.3 tonnes of cocaine from the area of a house being built by police officer Darren Davis, Mr. Matthews launched an internal investigation to try to weed out potential corruption from the force’s ranks.

This drug bust also was a factor in the commission of inquiry announced by former Governor Gus Jaspert, which is probing allegations including political corruption and abuse of public funds.

During his interview with the Beacon this week, Mr. Matthews said police “don’t have a role in the COI at all.”

Though he has met with the head of the commission, he said, he has not “had specific requests” for information from him.

Despite the challenges the police force has faced and the shifting currents in government and crime, Mr. Matthews said he leaves the department with an upgraded fleet of vehicles, refurbished infrastructure, more officers, revamped disaster response plans, a more stringent process for screening new recruits, and an active campaign to thwart the drug trade operating in the territory.

These measures should help his successor, Mark Collins, he added.

“My hope is I will be handing to [Mr. Collins] a better organisation than the one I inherited,” Mr. Matthews said.

Early ambitions

Mr. Matthews said he took up his role of police commissioner with an open mind, deciding to let the needs of the territory and of the force dictate what he would try to improve and accomplish.

He soon realised that many residents felt police officers were lacking sufficient presence in the community, and that there was a need to “modernise” the force.

To rectify this, Mr. Matthews didn’t just seek to boost the number of officers in the force and on patrol: He also aimed to ensure their fleet of vehicles was more conspicuous and better maintained, he explained.

“I realised that actually a part of your visibility strategy has to be about, ‘What does the fleet look like that your officers occupy?’” Mr. Matthews said.

Promotions

Early in his tenure, Mr. Matthews also recognised that the process for promoting officers was outdated, and that it caused suspicions amongst some members of the force who felt it wasn’t fair or transparent.

“We redesigned that completely,” he said. “We rewrote policy, we brought in external experts on how to assess fairly … and in an unbiased fashion.”

The result: More than 30 officers have been promoted from sergeant to constable during Mr. Matthews’ time as commissioner, he said.

But such efforts, which were broadly aimed at “professionalising and modernising” the force, were entirely upended when Hurricane Irma battered the territory in September 2017, he added.

Hurricane Irma

The storm left the police force fractured.

Many of the new cars purchased as part of Mr. Matthews’ modernisation campaign were destroyed or damaged, and in the first 24 hours after the storm he could communicate with only about 40 percent of his officers, he estimated.

At a meeting at the Dr. Orlando Smith Hospital after the storm passed, Mr. Matthews had to send runners to deliver information to officers stationed at the Road Town Police Station, he said. Almost all the inmates of Her Majesty’s Prison left the facility, and widespread looting broke out, though Mr. Matthews claimed that the extent of such crimes was not as widespread as was sometimes reported.

In the years since, Mr. Matthews said, he has factored some of the weaknesses of the Irma response into revised plans for post-disaster policing.

After working with the Department of Disaster Management, he is confident the force would have a “much more robust” response to future disasters, he added.

This is partly because the police have repaired much of their infrastructure, such as building up their fleet of vehicles, repairing their radio system, and purchasing satellite phones that they didn’t have in 2017, Mr. Matthews said.

In the event of a similar storm in the future, police cars would be stored in underground car parks, and officers, scattered around the territory waiting to deploy as soon as winds drop below 50 miles per hour, would rush to protect “critical infrastructure” such as banks, supermarkets and power stations, Mr. Matthews said.

Police have also reworked their search-and-rescue plans, which are aided by a newly available GPS system and a detailed photographic record of which houses are on which lots, according to the commissioner.

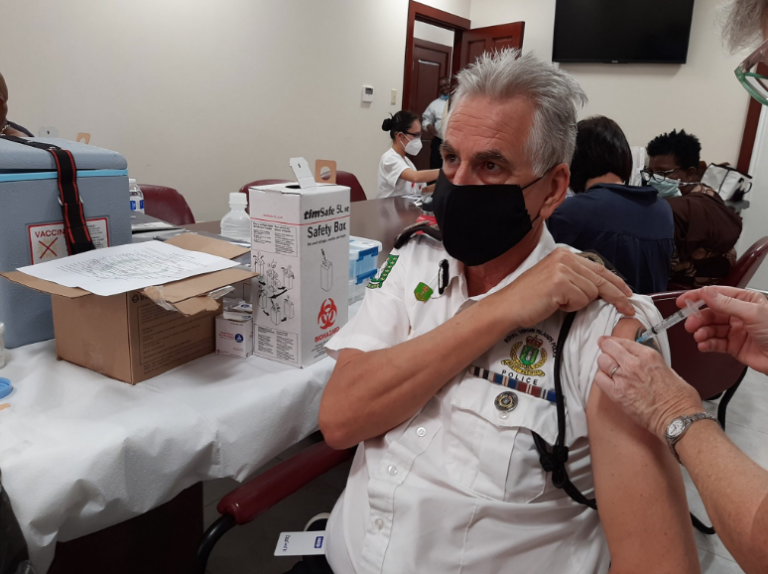

Michael Matthews takes the Covid-19 vaccine at the Road Town Police Station in an effort to urge residents to follow suit.

Michael Matthews takes the Covid-19 vaccine at the Road Town Police Station in an effort to urge residents to follow suit.

The pandemic

Much of the economic gains — particularly in the tourism sector — that the territory made during the recovery from 2017 hurricanes were again scuttled last year, when the Covid-19 pandemic reached VI shores and prompted a shutdown of the borders that continues to cripple the tourism industry.

These restrictions also created a challenge for police, who had to adapt their methods to meet the unprecedented circumstances.

At times, they used some of the tactics employed after the 2017 hurricanes, Mr. Matthews told the Beacon in April during the second 24-hour-a-day lockdown.

Although no state of emergency has been declared during the pandemic as after the 2017 hurricanes, many officers have worked shifts longer than 12 hours while some police services were stripped to free up more officers, Mr. Matthews said in April.

Police also had to strike a balance between arresting people who violated the curfew orders and not cluttering jail cells, where the virus could easily spread, he added at the time.

Additionally, they had to make slight adjustments to their conduct in order to social distance, such as standing outside the door of someone’s home rather than entering, or asking someone to roll down a window rather than exiting a vehicle during a traffic stop, the police commissioner said.

Border closures

One of the biggest measures taken to protect residents from the coronavirus, however, was the closure of the territory’s borders.

To enforce those rules, police worked with the Customs and Immigration departments in April to create the Joint Border Patrol Task Force, which pooled personnel and resources to block people from illegally entering and leaving the VI.

But the reopening of the seaports, scheduled for April 15, may “place a greater demand on customs and immigration [officers] to do their primary functions,” which could make fewer officers available for the joint task force, Mr. Matthews said this week.

But even if the task force is discontinued as the territory continues to reopen, the commissioner is confident that the lessons learned in “joint working” will be invaluable for years to come, he added.

Drug stockpiles

These efforts to guard the flow of people through the territory may have had unintended consequences on the drugs that also flow through these borders illegally, likely fueling a recent spate of violence that has left many residents concerned.

Though Mr. Matthews attributes the headline-grabbing recent drug busts in part to effective policing tactics, he also said on Monday that the tight restrictions likely make it more difficult to move illicit substances across borders.

The seizures of large quantities of drugs has been accompanied by violent crime in recent weeks. Though Mr. Matthews did not directly link the territory’s recent murders to confiscated drugs, he did say that drug-smuggling organisations have a hand in both types of crime.

“I have every reason to believe that some — not all, but some — of the recent homicides are directly connected to organised crime, and the drugs trafficking are performed by organised crime groups,” he said.

Since September, police have reported eight suspicious deaths, and Mr. Matthews on Monday confirmed that investigations into these killings are “very active.”

In October, Royden Sebastian was charged for the murder of George Burrows the previous month, but no charges have been laid in connection with the other deaths.

After the November drug bust, government employee Devon Bedford was charged in January in connection to a seizure of more than 259 kilograms of cocaine worth more than $25 million, and Paul Hodge was charged on March 8 in connection to a seizure of 535.5 kilograms of the drug valued at $53.53 from a vehicle he owns in Cane Garden Bay, police said.

Investigations into the drug networks active in the territory span international borders: In November, United States authorities arrested a Dominican Republic man who they said had travelled to St. John from Tortola, alleging that he is the leader of an international drug trafficking network responsible for the stockpile at the Tortola police officer’s residence.

On Monday, Mr. Matthews confirmed that the man, Ruben Reyes Barel, is wanted by VI police in connection to the November seizure, but he said he didn’t know whether US authorities still consider him to be the leader of the organisation.

Working together

But authorities in the VI do enjoy a close working relationship with law enforcement officials in the US when it comes to stemming the flow of drugs in the region, Mr. Matthews said.

While he cautioned that “we are two distinct jurisdictions with very distinct laws,” he said that VI officials often assist their US counterparts on request, sharing information whenever the law permits.

“We’re all fighting the same battle; we’re all fishing in the same pond,” Mr. Matthews said. Meanwhile, investigations focused on the movement of drugs within the territory continue as well.

Although police are treating the investigations into the bust at Mr. Davis’ residence and at Cane Garden Bay as two separate matters, Mr. Matthews said, officers keep an eye out for connections between different drug shipments, such as markings on the drug “load” and any indication of the route through which it was shipped, he said.

Internal probe

November’s high-profile bust also prompted police to look inward.

Soon afterward, Mr. Matthews announced an internal investigation into potential corruption within the force.

He did not comment on when that investigation might conclude or provide a detailed update, but he did say that he had recently briefed the National Security Council on the effort, which remains “very much a live matter.”

It’s possible that the probe may lead to arrests of officers, Mr. Matthews said, though he added that it is most important to put in place systems that make it easy to act on any suspicions.

One way that the force has already worked to lower the possibility of corrupt officers is to make the vetting process for new recruits more thorough, he explained.

As an example, he said, instead of just writing a letter to someone that a police applicant claims was a previous employer, officers often visit that employer for an in-person interview.

The force also has disseminated an internal code of ethics, and the “the third element,” Mr. Matthews said, is “to make it very, very clear to officers who are continuing to work in the force what the consequences are for people who cannot be trusted and who choose to go down the criminal path.”

Next steps

Mr. Matthews said he loves his job and he looks back on his five years in the VI with fondness. But after the tumultuous period through which he’s had to steer the police force, he’s ready for Mr. Collins to take over, he said.

And what’s next?

“I’ll probably sleep for six months,” Mr. Matthews joked.

Much of the commissioner’s time in the VI has been spent behind his desk in an air-conditioned office, so once he’s rested there’s plenty he wants to see and do in the territory before he and his wife return to the United Kingdom and reconnect with family, he said.

He has already begun handing over the reins to Mr. Collins, speaking with him virtually as Mr. Collins completes his 14-day quarantine.

Once Mr. Collins’ quarantine is over, the two will spend some time working alongside each other, allowing Mr. Collins to meet the people of the VI and to help “him get the best start possible,” Mr. Matthews said.

Successor

Mr. Matthews is confident in the capabilities of his colleague, who brings with him more than three decades of experience, including a four-years tint as the chief constable of Dyfed-Powys Police in Wales, following turns as the deputy chief constable in Bedfordshire and as borough commander of Walthamstow as part of London’s Metropolitan Police.

“From a policing and security perspective, it’s healthy to have a fresh set of eyes come in and look at where you are and where you need to go next,” Mr. Matthews said.

“I do think that we all have a limited time where we can only do so much. … It’s for others to judge what you’ve done, and I think more importantly, then to make sure others follow through and build on what you’ve done.