“Ghislaine, Is That You?”: Inside Ghislaine Maxwell’s Life on the Lam

“Ghislaine, is that you?” The woman making her way into the first-class cabin of a commercial flight from Miami to New York City was almost unrecognizable. Her attire, once stylish and attention grabbing, now seemed designed to deflect notice; her face, usually painted to perfection, was devoid of makeup.

There was a hint of gray in her signature black bob, and her days of starvation diets and charity-circuit appearances seemed far behind her. Wearing no traces of her glamorous New York life, much of it once provided by Jeffrey Epstein, Ghislaine Maxwell could have been anybody. Or nobody.

It was the spring of 2018, and it had been a decade since Maxwell’s former best friend and lover had served 13 months in a Palm Beach jail, with time free on work release, after pleading guilty to two charges, including soliciting a minor for prostitution. Maxwell, who had sold her Manhattan home—a five-story, 7,000-square-foot town house on East 65th Street—was essentially homeless. “No fixed address,” someone claiming firsthand knowledge of her situation would later say.

She might have spent the flight in anonymity had she not been spotted by a friend from New York who was sitting just behind her in the second row. “I was so shocked by her look,” the friend recalls.

“I didn’t recognize her.”The friend had known all the incarnations of Ghislaine Maxwell: the cherished youngest daughter of the British media baron Robert Maxwell, who died during a voyage on his yacht, Lady Ghislaine, under mysterious circumstances in 1991; the “broken bird” who returned to New York to move into a smaller apartment and launch a new life as a business consultant; the boldface-name Ghislaine, who seemed to be everywhere at once, so socially connected and sexually self-assured that she once hosted a dinner for East Side socialites on the fine art of giving a blow job, with dildos at each place setting; and the longtime companion of Epstein, a man even richer and more mysterious than her father.

She had served him for years, maintaining his homes, ranch, and private island, all the while allegedly recruiting and grooming a steady stream of girls for him and his powerful friends. Sometimes, federal prosecutors say, Maxwell herself took part in the sexual abuse.

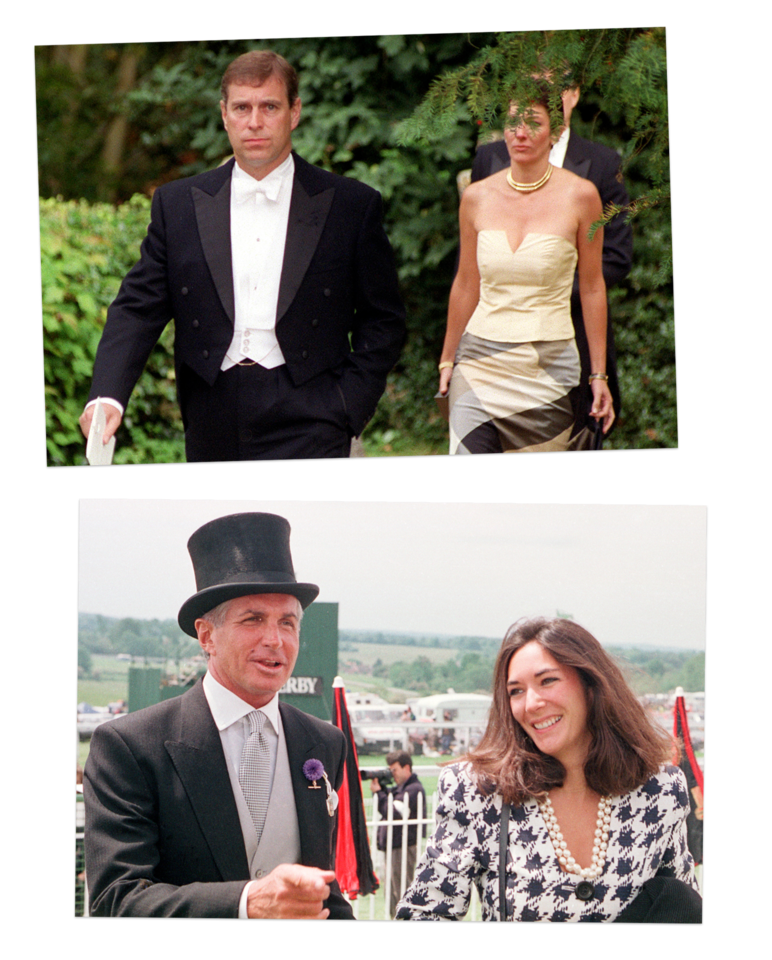

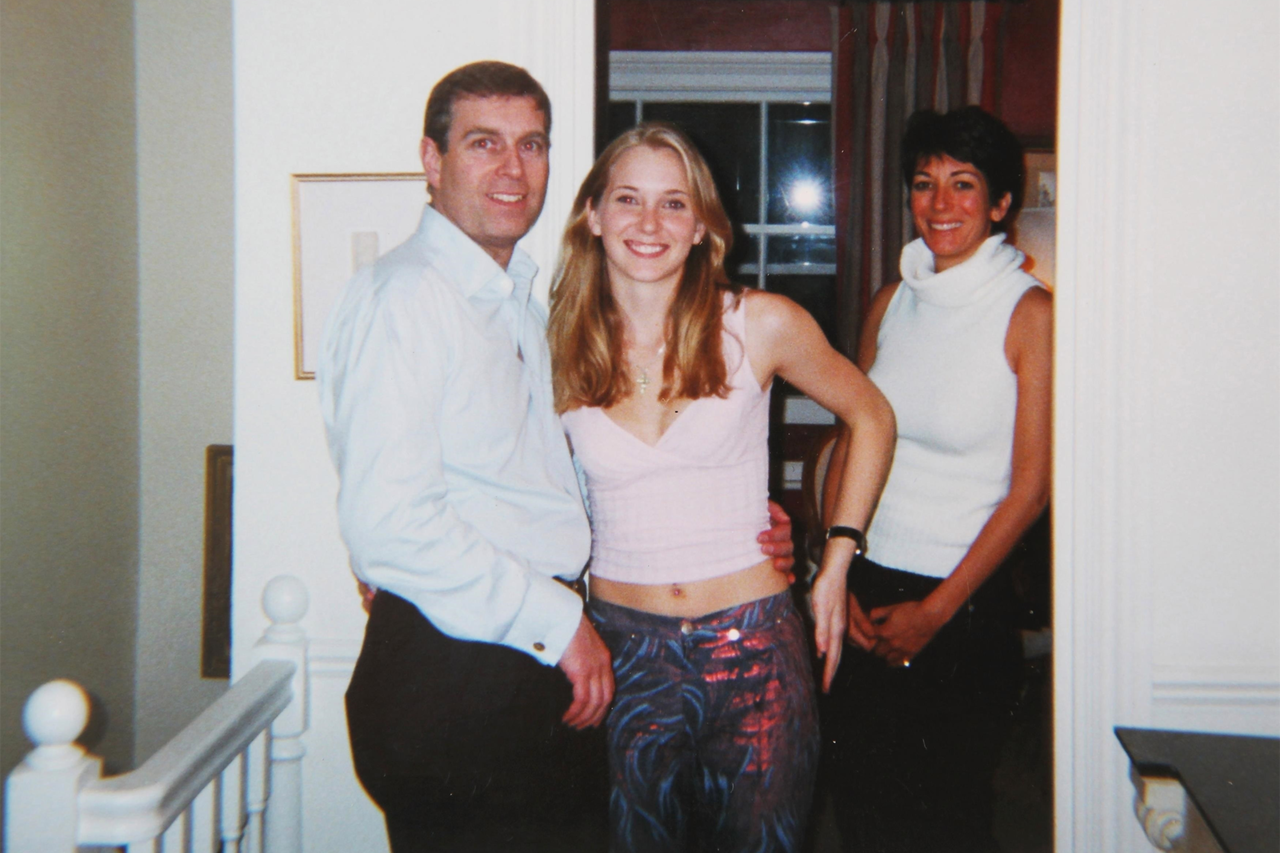

By the time the friend ran into her on the plane, Maxwell and one of Epstein’s victims, Virginia Roberts Giuffre, had settled a lawsuit in which Giuffre accused Maxwell of recruiting her as a “sex slave” for Epstein and Prince Andrew, among others, when she was only 17.

Now Maxwell was in the process of quietly withdrawing from the life she had made for herself. She shuttered the ocean-protection charity she had founded, the TerraMar Project, which left her with debts of $549,093. She even gave up her name, sometimes introducing herself to new acquaintances only as “G.” Yet here she was, on a commercial flight from Miami to New York.

For a moment, as the two friends chatted, the old Maxwell burst through: the Oxford-educated, knows-everybody-and-everything Maxwell, the woman who wanted to save the oceans but couldn’t seem to save herself from the men in her life. “Where are you living, Ghislaine?” the friend asked. “I lost touch with you.”

Maxwell suddenly went blank. “Oh,” she replied, “a little bit everywhere.”

“But where?” her friend pressed. Maxwell wouldn’t answer.

“Looking back,” the friend says now, “I personally think she knew that the shit was really about to go down.”

It went down quickly. Within a year, Epstein was exposed as one of history’s most notorious sexual predators, arrested on July 6, 2019, and found dead in a Manhattan jail cell five weeks later. After Epstein’s death, Maxwell disappeared from view entirely, leaving the courts, the media, his victims, and a transfixed and horrified public focused on a single question: Where in the world was Ghislaine Maxwell?

Everyone, it seemed, had a theory, each wilder than the last. She was said to be hiding deep beneath the sea in a submarine, which she was licensed to pilot. Or she was lying low in Israel, under the protection of the Mossad, the powerful intelligence agency with whom her late father supposedly tangled.

Or she was in the FBI witness protection program, or ensconced in luxury in a villa in the South of France, or sunning herself naked on the coast of Spain, or holed up in a high-security doomsday bunker belonging to rich and powerful friends whose lives might implode should Maxwell ever reveal what she knows—all the dirty secrets of the dirty world that she and Epstein shared.

“Maxwell is not gonna be able to hide,” David Boies, the powerful superlawyer who represents several victims who are suing her, declared confidently a few days after Epstein’s death, in August 2019. “There’s no place in the civilized world where she can go and not be found. And unlike Epstein, she does not have the massive resources that would be required to carve out a new life in some obscure place where she cannot be extradited from.”

But it’s a big planet for a citizen of three nations—the United States, Great Britain, and France—who speaks four languages fluently and has a world of connections. Almost a year after Boies’s statement, Maxwell remained at large, beyond the reach of attorneys, tabloid reporters, and a 10,000-pound reward from The Sun in London. “It’s a little bit like Elvis—you get lots of reports but they’re hard to verify,” Boies said in May.

“You have made efforts to locate her and have been unable to do so?” Judge Debra Freeman asked an attorney representing several Epstein victims in a crowded Manhattan courtroom on February 11. The attorneys were seeking a court order to serve Maxwell via alternative service, including email, after their attempts to find her had turned into what one of them called “a cat-and-mouse chase.”

“Yes, your honor,” replied the attorney.

The judge granted the request. But while the complaint apparently reached Maxwell, it provided no clue to her location. In late June, the tabloids placed her in Paris, where she was reportedly residing in a luxury apartment and walking the streets near the Israeli embassy with a “large patterned blanket” draped around her face and head—a scenario a friend of hers described as “drivel.”

“She could be anywhere,” said one person familiar with the lengths people went to track her down. “Russia, China, Singapore, the Middle East, England. She’s in some friend’s castle in the middle of nowhere. Or in a tent somewhere deep in some desert. Wherever she is, she’s on the down low.”

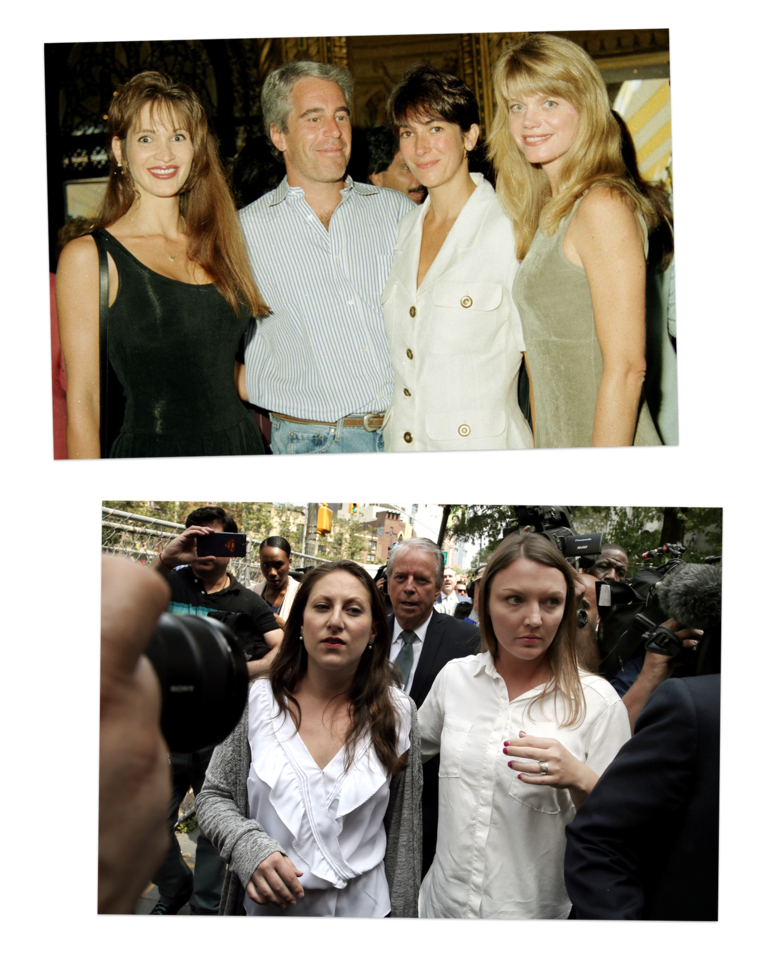

Maxwell’s year on the run came to an abrupt end in the early hours of July 2, when the FBI and New York Police Department arrested her in the small New England town of Bradford, New Hampshire. Prosecutors from the Southern District of New York charged her with four counts in connection with the sexual abuse of minors and two counts of perjury for lying under oath. Between 1994 and 1997, the years of her “intimate relationship with Epstein,” the indictment charged, she “assisted, facilitated, and contributed to Jeffrey Epstein’s abuse of minor girls.” One of the three unnamed victims was “as young as 14 years old when they were groomed and abused by Maxwell and Epstein, both of whom knew that certain victims were in fact under the age of 18.”

The indictment paints Maxwell as Epstein’s partner in crime, adept at the art of grooming victims for him. Her methods, prosecutors said, involved befriending “some of Epstein’s minor victims prior to their abuse, including by asking the victims about their lives, their schools, and their families. Maxwell and Epstein would spend time building friendships with minor victims by, for example, taking minor victims to the movies or shopping.”

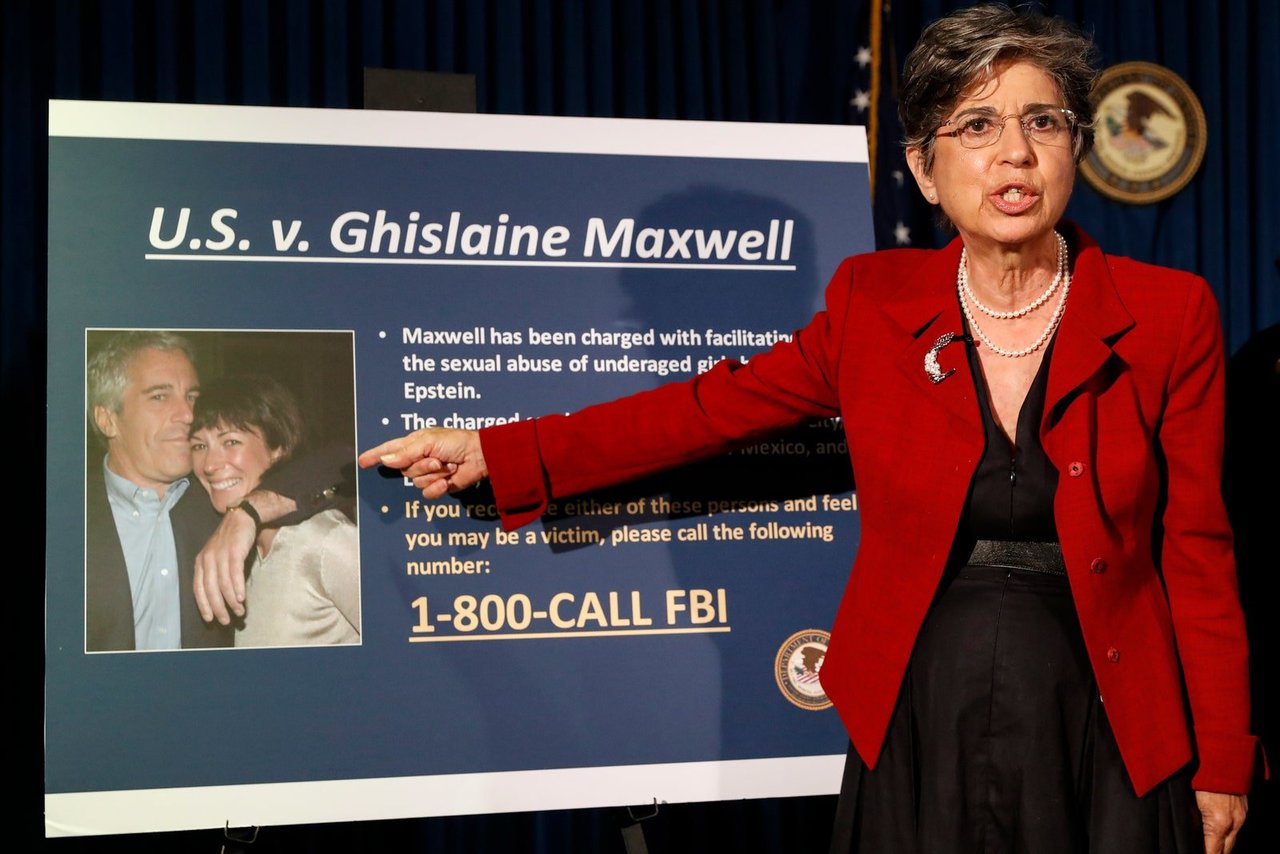

Maxwell “delivered them into the trap,” Manhattan U.S. Attorney Audrey Strauss said at a press conference the day of Maxwell’s arrest. “She pretended to be a woman they could trust. All the while she was setting them up to be sexually abused by Epstein and, in some cases, by Maxwell herself.”

Once the trap was laid and rapport established, Maxwell would then “try to normalize sexual abuse for a minor victim by, among other things, discussing sexual topics, undressing in front of the victim, being present when a minor victim was undressed, and/or being present for sex acts involving the minor victim and Epstein,” all of which “helped put the victims at ease because an adult woman was present,” according to the indictment.

Maxwell knew full well what Epstein planned to do, the indictment continued, “knowing that he had a sexual preference for underage girls,” and she sometimes “was present for and participated in the sexual abuse of minor victims.” Some of the acts of abuse, prosecutors say, took place at Maxwell’s London residence.

When Maxwell was finally brought in for a deposition under oath, in 2016, in the defamation case against her by Virginia Roberts Giuffre, she “repeatedly lied when questioned about her conduct.”

She did so, said Strauss, “because the truth, as alleged, was almost unspeakable.”

At the press conference, FBI assistant director William F. Sweeney Jr. described Maxwell as “one of the villains of this investigation,” who had “slithered away to a gorgeous property” in New Hampshire, where she was “continuing to live a life of privilege while her victims live with the trauma inflicted upon them years ago.”

It was not the first time in her life Ghislaine Maxwell went to ground. Her process of disappearing began, really, on a dreadful day almost 30 years ago, with a dead body floating in the sea.

Arms splayed out, face staring into the sky, enormous belly bobbing in the Atlantic just off the coast of Tenerife in the Canary Islands: That’s how Spanish police discovered the “naked, stiff, and floating” corpse of the British media baron Robert Maxwell on November 5, 1991. A helicopter hovered overhead, lowering its cable and straining to recover the cadaver, which weighed 310 pounds. Fifteen miles away was Maxwell’s 180-foot yacht—from which, according to various theories, he either jumped, fell, or was pushed—named Lady Ghislaine, after his 29-year-old daughter.

She had been his miracle baby, born on Christmas Day 1961. Two days after her birth, Maxwell’s eldest son suffered a car accident that would turn out to be fatal. “I’ve been told it means ray of sunshine,” Ghislaine once said of the origins of her French first name. The morning after the police helicopter lifted the bloated body from the sea, she flew in from London to be at her beloved father’s side.

To Ghislaine, her mother, three brothers, and three sisters, Robert Maxwell was Samson, tearing down the gates of Gaza, as he was depicted in a stained-glass window in their 51-room Oxford mansion: a titan of luck, impossible achievement, and unlimited wealth. “If Bob Maxwell didn’t exist, no one could invent him,” Labour Party leader Neil Kinnock would say.

Born Jan Ludvik Hoch into a Hasidic family in a tiny village in Czechoslovakia, he was so poor that he and his six siblings had to wear shoes in shifts. He evolved into a warrior, surviving the Holocaust, in which 300 of his immediate and extended family members perished, to join the Czech resistance. When his country fell to the Nazis, he fled to France and joined the British Army, fighting in bloody battles from Normandy to Germany.

After the war, he married the daughter of a prosperous British silk merchant, christened himself Robert Maxwell, and bought Pergamon Press, a publisher of scientific journals. It became the anchor of an empire that would, at the time of his death, include hundreds of companies, among them the publishing giant Macmillan and newspapers from The Mirror in London to the New York Daily News.

As big as or maybe even big-ger than his rival, Rupert Murdoch, Maxwell was a bombastic, demanding patriarch who dined with kings and presidents and exhibited a bottomless appetite for family, food, fortune, and fame.

Now he was dead, and it wasn’t long before the mighty house of Maxwell was exposed as a house of cards. Maxwell, it turned out, had pledged millions from his company’s pension funds to shore up his tottering empire, exposing his 32,000 employees to retirement ruin and racking up debts of nearly $5 billion.

The conspiracy theories multiplied: He committed suicide rather than face his financial crimes; he died aboard his yacht while engaged in sex with a mistress; he fell overboard during his regular postmidnight piss over the railings; he was murdered by British security agents panicked that he had taken possession of tapes that could incriminate the MI6 intelligence service in crime and espionage; he was injected with a poisonous syringe by frogmen sent by his Mossad spymasters to silence him from revealing their secret arms deals.

No one was more shocked and distraught at the revelations than Ghislaine Maxwell. She had always been, as a friend told The Times of London, “the life and soul of the party wherever she wanted to go in the world and never had to worry about money.” Now she was the shattered child of a man described as a monster, his name forever equated to scandal. “She was catatonic,” the friend said. “It hit her in a way that scared people.”

She was weeping when she boarded her father’s yacht, weeping when her mother asked her to address the media throngs, weeping as she rehearsed her speech over and over. Every time she came to the words my daddy, she began to shake and tremble. “I felt sorry for her because she was daddy’s girl,” recalls former Mirror photographer Ken Lennox, who was aboard the Lady Ghislaine that morning and who helped draft Maxwell’s remarks. “She obviously adored her dad.”

But when she finally stepped before the reporters, she had somehow collected herself. “She raised her hand, an imperious gesture she had seen her father use to quieten a media frenzy,” according to an account in Robert Maxwell: Israel’s Superspy. “How did your father die?” a journalist shouted at Maxwell. She looked down at the mob and “in a loud and clear voice she spoke. ‘I think he was murdered.’ ”

After Robert Maxwell’s burial on the Mount of Olives in Jerusalem, the family returned to London, where they faced a frenzy in the press. The British tabloids, which once enriched the Maxwell family, now seemed intent on destroying it. Maxwell’s widow grew “numb from the savage public battering,” Vanity Fair reported at the time. “People were calling her husband ‘rogue,’ ‘crook,’ ‘bully,’ ‘thief,’ ‘megalomaniac,’ ‘gangster.’

They told lurid tales of his sex orgies.… They painted a portrait of an erratic and cruel tyrant, one who used Turkish towels for toilet paper.” Maxwell’s widow, the elegant and erudite Elisabeth Jenny Jeanne Meynard Maxwell, went underground, moving surreptitiously from lawyer to lawyer. “I’ve had to live by night and sleep by day to avoid the reptiles,” she said.

Ghislaine Maxwell was hunted by the tabloids too. “There’s a story that the Maxwell name was so detested in London that she had to walk around in a blond wig so people wouldn’t recognize her,” an unnamed “prominent New York socialite” who knew Ghislaine reportedly told the New York Post.

Hoping to launch a new life, she returned to New York City, where she had served as her father’s ambassador to America in the days when he hoped his daughter might marry her friend John F. Kennedy Jr., binding two great dynasties into one. Now, forced to vacate her spacious company-provided residence, she moved into a small apartment. When a friend came to visit, Ghislaine told her, “They took everything—everything—even the cutlery.”

“She was broke, the family was broke,” the friend recalls. “This girl who was brought up in luxury, and—bang—everything was taken from them, and she came to the United States to begin again.”

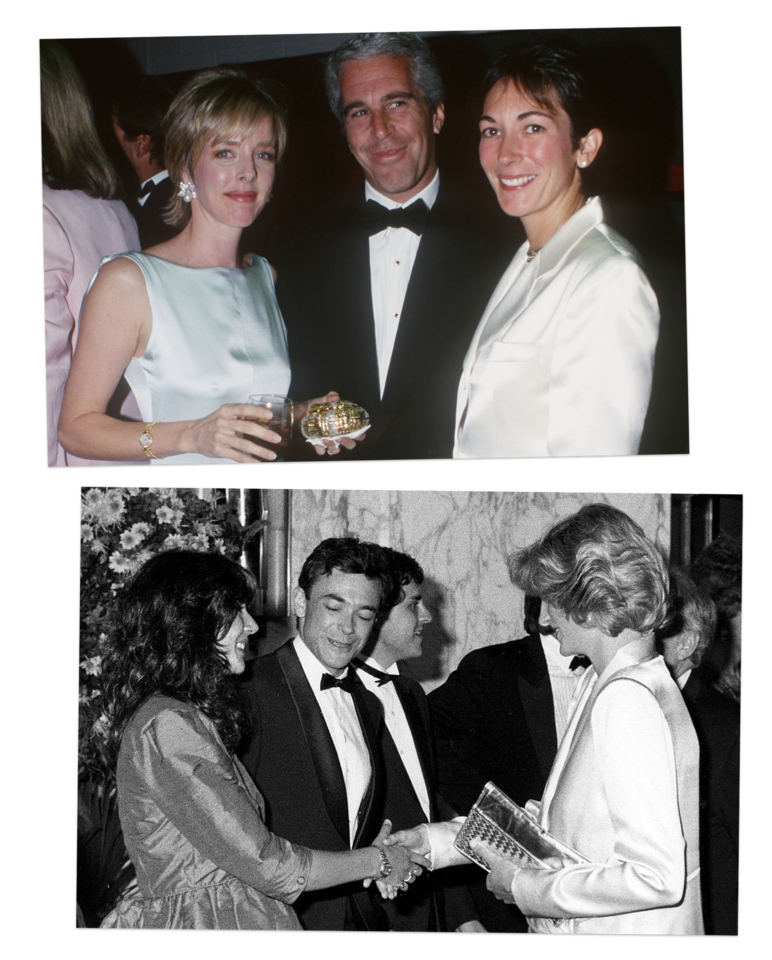

Ghislaine Maxwell’s reinvention didn’t take long. In November 1992, one year after the death of her father, she was reportedly seen boarding the Concorde from London to New York. “Unnoticed by almost everybody, traveling with her was a greying, plumpish, middle-aged American businessman who managed to avoid the photographers,” reported the Mail on Sunday, one of her father’s rival newspapers. “It is to this man that 30-year-old Ghislaine has turned to ease the heartache of her father’s shame.

“His name is Jeffrey Epstein.”

At first, Ghislaine seemed to keep quiet about her new romance, even with friends. One day she invited someone who had known her during her London days to visit her in New York. He was shocked when she met him at the door of the largest private residence in the city, a gilded seven-story town house on East 71st Street.

“Whose house is this, Ghislaine?” the friend asked. “Who lives here?”

“My friend,” Maxwell replied.

“Well, is he banging you?” the friend demanded. “What’s the scoop here?”

Maxwell wouldn’t say. “She would never bloody let on,” the friend recalls. “I didn’t get further than the drawing room. She was very, very cagey about me being there. I didn’t have an affair with her, but I certainly chased her for a bit. She was sexy and fun. I guess if Epstein had seen me there, he would have been really pissed off to have some young dude who was trying to shag his friend.”

Maxwell didn’t mention the relationship to Hello! magazine when it featured her on its cover in February 1997, in her first interview since her father’s death. She was now “far from the ever watchful eye of the British press,” the magazine reported, and had become a “business consultant,” living and working out of her East Side apartment with Max, a Yorkshire terrier named after her father.

“She is proud of the fact that her new life is all down to her own hard work and has her elegant apartment to show for it,” the magazine added. One day, Maxwell said, she would “get married and have kids. But it has never been a focus: My focus is my business.”

Her business, first and foremost, was keeping Jeffrey Epstein happy. He shared much with her father: a humble origin, a vast fortune derived by mysterious means, even rumors of ties to the Mossad and other intelligence agencies. Like Robert Maxwell, Epstein also attached himself to a woman of higher status. In those days, Manhattan was party central, a place where connections were made at night, person to person.

“Ghislaine was at the epicenter of all that,” says Euan Rellie, a British investment banker who knew Maxwell in both London and New York. “She befriended everybody and had a massive Rolodex of influential people.”

Those connections proved pivotal to Epstein. “I always say that Ghislaine helped Jeffrey become who he became,” says one of Epstein’s victims. “He had the money, but he didn’t know what to do with it. She showed him.” Epstein built a 21,000-square-foot mansion on a 10,000-acre ranch in New Mexico, which he boasted made his New York town house “look like a shack,” and named it the Zorro Ranch.

He also acquired a 72-acre island in the Virgin Islands and an 8,600-square-foot home in Paris, which is said to have featured a specially built massage room. Maxwell is said to have shared Epstein’s bed in each of the residences, as his girlfriend, before moving on to become his “best friend,” as he called her in Vanity Fair. (“When a relationship is over, the girlfriend ‘moves up, not down’ to friendship status.”)

Maxwell soon had a bed of her own in a five-story town house on the Upper East Side, tended by a live-in couple who served as her housekeeper and driver, two secretaries (one for her and a second for Jeffrey), and an immense budget for the six properties she was managing for Epstein. She had found a path back to the lifestyle she’d lost when her father died. “She was used to living very well,” says a friend who knew her then. “She didn’t want to go back to where she was.”

She wore a large diamond ring Epstein had given her, which she called her engagement ring, according to one of Epstein’s victims. “She would say things like she was the only one who Jeffrey slept with,” the woman says. “I know that she would have died to marry him. She would have done anything for him. He trumped everybody and everything.”

Maxwell was expected to drop everything to serve Epstein. “Ghislaine was one of the first people in New York to walk around with a cellular phone, and she would very ostentatiously put it on the table at lunch,” says Christopher Mason, the British writer and TV host. One day, the phone rang while Maxwell was hosting a friend for tea in her apartment.

“That was Jeffrey,” she told her friend. “He has the flu, and he wants me to go and get the best chicken soup in New York and take it to his house.’

“Ghislaine, he has people on staff!” the friend said. “Can’t he send one of them?”

“No, no,” Maxwell said. “It has to be me.”

Every few days, it seemed, Maxwell’s phone would ring and Epstein would inquire about the weather in Palm Beach, New Mexico, the Virgin Islands, or Paris. Ever-efficient Maxwell would spring into action, consulting the forecast, then alerting the pilots to ready the plane to fly to wherever skies were clearest. Then they were off: Maxwell organizing armies of staff in the various locations, coordinating everything, almost as demanding and bombastic as her father. “She would call people her minion, piglet, polyp,” says one victim. “So you felt like you were nothing.”

She had to keep everyone in line, because one misstep would unleash the wrath of Epstein, one of the few people who could make Maxwell cry. “He would be screaming over the phone,” recalls a victim, “and she would burst into tears.” The woman who once had everything money could buy, only to lose it all because of a man, was once again living a life of luxury.

All she had to do to keep it was to give the monster what he wanted. And what he increasingly wanted were women—“on the younger side,” as Donald Trump would say—for whom Maxwell is said to have searched everywhere: spas, massage parlors, parties. Once she found them, she would invite them to “tea” at Epstein’s mansion.

“She was his gatekeeper into civilized society,” says Rellie. “Every 20- to 30-year-old interesting pretty new girl that showed up in New York, Ghislaine would get to know them and invite them to tea with Jeffrey.”

The teas soon grew into dinners, and the guests rose in stature. “It all felt very frenzied and frothy,” recalls Mason. “It seemed like everyone I knew knew her. Ghislaine was always on her way to have a meeting with someone like Bill Clinton. Everything was with the idea that she was staggeringly well connected.”

Her New York town house became a social nexus; one dinner party’s 80 guests included members of the Kennedy and Rockefeller clans, “along with the requisite sprinkling of countesses and billionaires,” reported The Times of London in 2011. Maxwell had become “a modern-day geisha” in a “domain filled with the richest people in the world—some of whom are good guys, and some of whom are bad—and who think they are above the law. It’s a world frequented by young half naked girls in bikinis, billionaires and lavish lifestyles, but it borders on the grotesque. You are never really sure what is going on behind closed doors.”

One Christmas, a very big billionaire threw a very big party in his very big apartment. Maxwell swept in and scanned the room, her eyes falling on two young sisters.

“Oh, my God, look at those girls!” Maxwell exclaimed, according to a friend. “I didn’t realize that they’re so beautiful! Can you introduce me to them?”

“Ghislaine, why would you want to meet them?” the friend asked. “Wouldn’t you rather meet their parents?”

“I’d like to meet them because I know Jeffrey would like to meet them,” Maxwell explained.

“And that,” the friend recalls, “is when I realized something was very strange.”

Maxwell consistently denied ever soliciting underage girls for Epstein. And she began trying to distance herself from him long before he went to jail. In the early 2000s, she spent time in California with a man many times richer than Epstein: Ted Waitt. He lived in a seven-bedroom, 14-bath mansion in La Jolla, and they sailed aboard the 240-foot mega-yacht she helped him purchase, the Plan B.

It was equipped with a helipad, Jacuzzi, elevator, gym, and onboard submarine, which Maxwell was soon licensed to pilot. “After she became his girlfriend,” according to the New York Times, “Mr. Waitt shaved his head, started wearing tinted glasses, and became a virtual doppelgänger for Jason Statham.” (Waitt could not be reached for comment.)

Epstein, who some say felt threatened by the relationship, convinced Maxwell to return to work for him in 2004. In court papers, Maxwell’s attorneys stated, “From approximately 1999 through at least 2006, Maxwell was employed by Epstein individually, and by several of his affiliated businesses.” She reportedly continued to accept rides on Epstein’s plane until at least 2006, along with his money.

“In some of the litigation we brought against her in 2015, 2016, and 2017, Epstein was paying her legal fees,” says David Boies. The last known photo of them together is from a benefit for Wall Street Rising in 2005. In the photo, Epstein has his arm around Maxwell’s neck, pulling her close. A broad smile lights up her face.

Away from Epstein, Maxwell was reborn, appearing on CNN, giving a speech at a TED event, and speaking nine times before the United Nations, having refocused her attention to something that she felt desperately needed saving: the crypt of her father, the sea. In September 2012, she founded the Terra-Mar Project “to build a global community to give a voice to the least explored, most ignored part of our planet—the high seas.” Her “founding citizens” included Virgin Group owner Richard Branson.

But process servers were now on her trail, dispatched by an attorney named Bradley Edwards, who was determined to depose her about her relationship with Epstein. In what he would call a 12-year campaign to bring Epstein to justice, Edwards became convinced that Maxwell was “the most important of all,” the key to unlocking Epstein’s secret world, the “one woman, who by all appearances, Epstein treated as his equal.” He hired investigators to track her and succeeded in serving her at the Clinton Global Initiative annual meeting in New York in September 2009. “To say she was upset about being publicly served at this function is an understatement,” Edwards later wrote.

As the July 2010 date for Maxwell’s deposition approached, her attorney called Edwards to explain that “Maxwell’s mother was very ill, so Maxwell was leaving the country with no plans to return to the United States.” A few weeks later, Edwards opened People magazine to find a photo of Bill Clinton walking his daughter, Chelsea, down the aisle at her July 31 wedding in Rhinebeck, New York.

“Holy shit!” Edwards would later write. “Who was front and center on the aisle? Ghislaine Maxwell.”

It would be six years before attorneys for a different accuser would get the chance to depose Maxwell at last. Virginia Roberts was a 17-year-old changing-room attendant at Donald Trump’s Mar-a-Lago Club when, she said, Maxwell recruited her as a traveling masseuse for Epstein. She had first told her story to the FBI and the Daily Mail in 2011. In December 2014, using her married name of Virginia Roberts Giuffre, she filed a motion in the Southern District of Florida describing Maxwell as Epstein’s “primary coconspirator and participant in his sexual abuse and sex trafficking scheme.”

Maxwell reacted with fury, issuing an “urgent” statement to the media dismissing Giuffre’s claims as “defamatory” and “obvious lies.” Giuffre, in turn, sued Maxwell for defamation in federal court in New York, a lawsuit “widely viewed as a vessel for Epstein’s victims to expose the scope of Epstein’s crimes,” the Miami Herald would later report.

The depositions took place over several days, led by Roberts’s attorneys David Boies and Sigrid McCawley. Maxwell vociferously proclaimed her innocence, at one point banging her fists on the table. The indictment charges that during these depositions, on April 22 and July 22, 2016, she committed two counts of perjury.

“Did Jeffrey Epstein have a scheme to recruit underage girls for sexual massages?” she was asked.

“I don’t know what you’re talking about,” she replied.

“Were you aware of the presence of sex toys or devices used in sexual activities in Mr. Epstein’s Palm Beach house?”

“No, not that I recall,” she answered.

She said she was “not aware of anybody that I interacted with, other than obviously [the plaintiff] who was 17 at this point.” She said she “wasn’t aware that [Epstein] was having sexual activities with anyone when I was with him other than myself.” And she said, “I have not given anyone a massage.”

Faced with the same kind of tabloid frenzy that accompanied the death of her father, Maxwell opted for the same escape route: She uprooted herself and tried to start over. After selling her Manhattan town house and disposing of many of her possessions, she moved to Manchester-by-the-Sea, a quiet village 30 miles north of Boston.

There she lived for a time in the $3 million, five-bedroom colonial home of Scott Borgerson, a handsome data analyst who focuses on maritime trade. Maxwell and Borgerson had met in 2013, when they were both speaking on panels at the Arctic Circle Assembly in Reykjavik. (Maxwell appeared on “Climate Change: A Plan for Action,” a panel whose experts included former vice president Al Gore, who called in via video.)

In the spring and early summer of 2019, when the U.S. attorney in the Southern District of New York reopened the criminal investigation into Epstein, Maxwell was far away and seemingly unconcerned. On June 6, she met with Prince Andrew in Buckingham Palace. “She was here doing some rally,” Prince Andrew would later say in a disastrous interview on BBC’s Newsnight. “Some rally” was an understatement.

Maxwell had been invited to participate in Cash & Rocket, an annual charity road rally in which 80 women—including Paris Hilton and Topshop heiress Chloe Green—drove 1,500 miles over four days in a caravan of red Ferraris, Alfa Romeos, and Bentleys from London to Paris to Geneva to Monte Carlo. In screaming red jumpsuits, Maxwell and her copilot, Annette Mason, the wife of Pink Floyd drummer Nick Mason, drove car No. 28, a cherry red Alfa Romeo, in shifts, stopping for the rally’s parties and photo ops along the way.

Following a pre-tour Masquerade Ball in London’s Victoria and Albert Museum, the participants hit the road, and Maxwell could be seen smiling in the party pictures: in white at the Elegant in White dinner at La Reserve in Geneva; in a sparkly red dress and dangly earrings at the Red party at the Yacht Club de Monaco. These party photos would be her last. Cash & Rocket would soon scrub Maxwell’s photo from its website, claiming she had been invited by one of the drivers, not the rally itself.

After the rally, she disappeared.

On July 6, Epstein was arrested by federal agents after his jet landed at Teterboro Airport from Paris. The FBI raided his mansion and charged him with sex trafficking of minors, stemming from incidents between 2002 and 2005. With his arrest, attention began shifting toward Maxwell. “Epstein’s pimp girlfriend, Ghislaine Maxwell, a very well-connected Brit socialite cannot just walk free,” the actress Ellen Barkin tweeted the day after Epstein’s arrest. “This woman is his pimp. She pilots planes to and from the island. I know because she told me.”

Now she was back on the tabloid radar. The Daily Mail would soon dispatch a team to Manchester-by-the-Sea on a tip that Maxwell was living there. Helicopters hovered over the village. Neighbors faced media interrogations. Maxwell’s older sister, Christine, was photographed packing bags into a car, and Scott Borgerson was snapped walking a dog believed to belong to “G”: a vizsla, the aristocratic breed of Hungarian sporting dog Maxwell had once shown at Westminster. (“I’m home alone with my cat,” Borgerson later told the New York Post. “She’s not here, I have no idea where she is.… Nobody wants to be close to this radioactive situation.”)

In the Netflix documentary Jeffrey Epstein: Filthy Rich, several victims claim that Maxwell not only lured them into Epstein’s web, but also fondled or sexually abused them. When asked about Maxwell’s role in his sex crimes during a deposition, Epstein invoked the Fifth Amendment at least 14 times. She doesn’t appear to have visited him during his 13-month stay in the Palm Beach County Jail in 2008 or during his 2019 incarceration in New York.

On the morning of August 10, Epstein was found dead, hanged in his jail cell. Fashioning a noose from his orange prison bedsheet, police said, he tied it around his neck, fell to his knees, bent forward, and strangled himself, along with his secrets. His body was discovered at 6:30 a.m. “Noel [the guard] sent me burnt food,” Epstein reportedly wrote in his suicide note. “Giants bugs crawling over my hands. No fun!!”

Somewhere far away, Maxwell awoke to the news. Her year of no fun was about to begin.

The day before Epstein committed suicide, a federal court unsealed 2,000 pages of evidence from the defamation case brought by Virginia Roberts Giuffre. Maxwell strides through the pages, accused of being Epstein’s madam and mistress: allegedly recruiting girls to satiate what Epstein called his required three orgasms a day (“It was biological, like eating,” one of his victims testified); instructing the girls on the fine art of erotic massage (“She was implying that I did not get Jeffrey off, and so she had to do it,” the same victim said); and allegedly even participating in sex acts along with Epstein.

Her name appeared on message slips that investigators pulled from Epstein’s trash in Palm Beach, and on the flight manifests of Epstein’s Boeing 727, dubbed “the Lolita Express.”

Now, with Epstein’s arrest followed swiftly by his death, Maxwell was on her way to becoming one of the world’s most wanted women.

Then, the strangest thing happened: She supposedly emerged in broad daylight at, of all places, the In-N-Out hamburger franchise on Cahuenga Boulevard in the San Fernando Valley.

If ever there were a day for Maxwell to lie low and stay out of sight, it was Monday, August 12, a day when her name was being featured prominently in headlines and news broadcasts worldwide. “The death of Jeffrey Epstein is putting new attention on his alleged coconspirators, who could still face charges,” CBS reported that day. “The number one person on that list is Ghislaine Maxwell, who’s accused of finding teenage girls for Epstein and his friends.”

And yet here was Maxwell—or at least her image—sitting outdoors at a Formica-topped table, in a baby-blue hoodie and capri pants befitting a suburban L.A. housewife. Before her on the table was a hamburger, a shake, and an order of hand-cut fries. She had apparently brought along a friend’s dog and something to read, The Book of Honor: The Secret Lives and Deaths of CIA Operatives, by Ted Gup, whose Amazon ranking was about to skyrocket more than 300,000 places, to No. 103 on the best-seller list, because of what was about to occur.

Three days later, photos of this humdrum tableau appeared in the New York Post. According to the accompanying article, a fellow diner had simply recognized Maxwell and taken her picture. Is that really what happened? Were these actual photos of Ghislaine Maxwell eating a burger and reading a book two days after the man she spent much of her life with died in disgrace behind bars?

Or were they, as many would contend, photoshopped fakes designed to throw the bloodhounds off her trail? Those arguing against their authenticity cited a poster for the movie Good Boys on a bus stop in the background that records show had never been displayed there, questioned why Maxwell had two trays and two cups if she was eating alone, and pointed out that the metadata in one of the images published on nypost.com suggested that it had been supplied by a Los Angeles–area attorney friend of Maxwell’s—who just so happens to be the owner of the dog.

Nevertheless, people flocked to the In-N-Out to take pictures of the table where Maxwell had supposedly dined. Theories of the deeper meaning behind the photos began circulating. The New Yorker suggested it was a brazen come-find-me message, a taunt to the world on her tail, a real-life version of Where’s Waldo? “There appeared to be, in other words, a distinct possibility that Maxwell was fucking with us,” wrote Naomi Fry. “ ‘Here I am,’ her face seemed to say. ‘Figure this out.’ ”

After that, Maxwell once again disappeared. But where? Was it possible Sky News got it right when it placed her on the southern coast of Brazil, citing an unidentified American former police officer who had allegedly traced phones belonging to Maxwell and the modeling agent Jean-Luc Brunel, another Epstein associate? Or was she in London, as evidenced by an affidavit she signed in her elaborately indecipherable signature, filled with loops and swirls, on November 22, 2019, listing her location as Half Moon Street in the affluent Mayfair neighborhood? Or did she sign it from afar?

She was “both everywhere and nowhere,” bemoaned The Guardian.

Then something happened that forced Maxwell to take new precautions. “Death threats,” said a friend who claimed knowledge of Maxwell’s situation. They arrived by social media, email, phone, text, and postal service, a chorus of anger intent on revenge. The threats began in earnest with Epstein’s arrest, multiplied with his death, and accelerated in the months that followed. They soon became a routine part of her life.

“It’s not a specific threat,” the friend said. “It’s the volume of threats. These are credible threats. That’s a term that law enforcement uses—credible threats. So you take appropriate action.”

A professional security firm was hired, its plainclothes operatives said to be veterans of intelligence and law enforcement agencies. “Maxwell receives regular threats to her life and safety, which required her to hire personal security services and find safe accommodation,” reads the complaint she filed in the Virgin Islands last March, seeking payment of her expenses from Epstein’s estate, reportedly valued at more than $600 million. “These expenses will be ongoing.”

Maxwell’s effort to tap Epstein’s estate to cover her security costs prompted new outrage. “It is absolutely appalling that Ghislaine Maxwell…is seeking to drain funds from the very estate that should be paying the Epstein victims’ claims,” Sigrid McCawley, attorney for Giuffre and other victims, said in a statement.

“We’ve had reports of her being in the South of France, Northern California, in the U.K., Israel, and maybe she’s moved around in all those places, but we don’t really know where she is now,” David Boies said in May. By then, Maxwell had become such a phantom that even some of her own attorneys would contend that they didn’t know her physical location and communicated with her primarily via email.

Imaginations ran rampant; theories multiplied. It was during this time that a friend came forward to Vanity Fair not with a sighting but rather with a description of Maxwell’s lifestyle undercover. It was an incognito existence of revolving residences and long runs on neighborhood roads. But her once-opulent life had been stripped down to the bare essentials: iPhone, iPad, laptop, casual clothing, and an inexpensive pressure cooker with which the friend said she emulated her Cordon Bleu–trained mother’s French recipes: beef bourguignon, red cabbage and apples, leek soup.

Every day, sometimes on public roads and hiking trails, she went for a run. If there was a pool available, she swam laps. Before gyms shut down, she boxed regularly, pounding away at a punching bag.

“The whole point of security is you don’t set a routine,” said the friend. At the end of the day, she usually exercised again, lifting weights or stretching while she watched the news. Afterward, she turned off the television for the night. Instead, she cooked and read, usually biographies. Her bedtime selections, according to the friend, included The Churchill Factor: How One Man Made History, by Boris Johnson, and Relentless Pursuit: My Fight for the Victims of Jeffrey Epstein, by victims attorney Bradley Edwards, in which she is prominently featured. Then it was lights out for her nightly five hours of sleep.

The only thing predictable about Maxwell’s life was her work, the friend said: speaking each day with her attorneys to hash out her defense in the cases against her. Maxwell had assembled a team of criminal and civil defense lawyers in New York, Colorado, the U.K., and the Virgin Islands, all typically ranging in fees from $500 to $1,500 an hour. “Her life is lawyers,” the friend said. “She speaks to lawyers and blood relatives. That is her universe. Defending all of these cases is a full-time job.”

At least three women have included Maxwell as a defendant in civil suits against Epstein’s estate for damages from sexual abuse. One is Annie Farmer, whose lawsuit states that Maxwell and Epstein subjected her and her sister Maria to “a scheme for manipulation and abuse of young females.” Annie was just 16 in 1995, when Epstein flew her from Arizona to New York.

The sexual abuse began there and continued at his New Mexico ranch. Epstein later offered Maria, then 26, an “artist-in-residence” opportunity at a 10,600-square-foot residence in billionaire Les Wexner’s Ohio compound, where she was sexually abused by both Epstein and Maxwell, according to the lawsuit.

On August 27, Annie Farmer appeared alongside 15 other accusers at a federal court hearing in New York. Epstein had died two weeks earlier, and an empty chair sat ominously at the defendant’s table as his accusers poured out their emotions, detailed their abuse, and demanded justice. “Jeffrey Epstein, Ghislaine Maxwell not only assaulted [Maria], but as we’ve heard from so many of the brave women here today, they stole her dreams and her livelihood,” Farmer told the crowded courtroom.

“The fact that I will never have a chance to face my predator in court eats away at my soul,” Jennifer Araoz said at the hearing. She accused Epstein of raping her when she was a 14-year-old high school student. “They let this man kill himself and kill the chance for justice for so many others in the process, taking away our ability to speak.” Days after Epstein’s death, she sued Maxwell, Epstein’s estate, and others, claiming that “Defendant Maxwell participated with and assisted Epstein in maintaining and protecting his sex trafficking ring, ensuring that approximately three girls a day were made available to him for his sexual pleasure.”

And now, following her arrest, she faces criminal charges. According to the detention memo filed by the Southern District of New York on July 2, Maxwell began “hiding out in locations in New England” in July 2019 and making “intentional efforts to avoid detection including moving locations at least twice, switching her primary phone number (which she registered under the name ‘G Max’) and email address, and ordering packages for delivery with a different person listed on the shipping label.”

If convicted, Maxwell faces up to 35 years in prison, and prosecutors arguing to deny her bail invoked her history of globe-trotting and apparent access to secret stashes of money. In the last three years, she took at least 15 international flights to “the United Kingdom, Japan, and Qatar,” according to the memo. She also had 15 different bank accounts from 2016 to the present, “and during that same period, the total balances of those accounts have ranged from a total of hundreds of thousands of dollars to more than $20 million.” She allegedly made transfers of “hundreds of thousands of dollars at a time.”

They finally found her in a four-bedroom, 4,365-square-foot home on a 156-acre wooded lot that she “acquired through an all-cash purchase in December 2019 (through a carefully anonymized LLC) in Bradford, New Hampshire, an area to which she has no other known connections.” The home is reportedly called Tuckedaway, and an online listing describes it as “an amazing retreat for the nature lover who also wants total privacy.” The sale price was $1,070,750.

Before Maxwell was arrested, I asked the friend who claimed to know her situation a question: “How does she see her future?”

When Maxwell was asked this question by Hello! magazine in 1997, she was 35 years old and starting over again in New York. “I am optimistic about my future,” she said, “and believe things will continue to improve for me as time passes.”

Now that time is gone, along with Jeffrey Epstein.

“I don’t think she sees there is a future,” came the reply.