Paul Merson: ‘Gambling is a horrible addiction. Your career passes you by’

A few minutes before Paul Merson tells the surreal story which makes him cry, in a beautiful but broken memory, he looks at me intently. “It’s been 36 years of pure madness,” Merson says as he reflects on the gambling disorder which, coupled with alcoholism and a brief but ruinous addiction to cocaine, has scarred his life.

Merson won two league titles and three cups with Arsenal, while playing some visionary football which he produced again for Aston Villa. He won 21 caps for England, played in the 1998 World Cup and, now, at the age of 53, he is a much-loved, or often cruelly mocked, member of Sky Sports’ Saturday Soccer panel alongside his close friend Jeff Stelling.

But, as Merson makes plain in his endearingly candid way, he has an illness above all else. He has lost more than £7m to betting companies but, as he stresses, the real cost has nothing to do with money. “If someone lived in my head they would think: ‘How did you even get through those 36 years?’ People go: ‘Oh, you lost all that money.’ But the money is irrelevant.’ You lose time. Time just goes and that breaks my heart more than anything.

“People ask: ‘What was it like when you won so much at Arsenal and played for England? I don’t know. All I remember was winning the league at Portsmouth. I wasn’t drinking, I wasn’t gambling too much and I sucked it in. I remember one game we played Millwall away [in March 2003]. Portsmouth and Millwall don’t like each other and so none of our fans were allowed in. I also remember having 30 grand, in cash, to give to someone after the game.”

Even if this was one of his less wasteful years, Merson was still so lost in his gambling maze that paying off £30,000 in bad debts remained a routine problem. Harry Redknapp, his manager at Portsmouth, was taken aback. When they couldn’t lock the away dressing room at Millwall, Redknapp had to look after Merson’s possessions. “Harry said: ‘What is it, Merse? A watch?’ I said: ‘No, I’ve got some money.’ Harry shoved 30 grand down his big, baggy tracksuit bottoms.

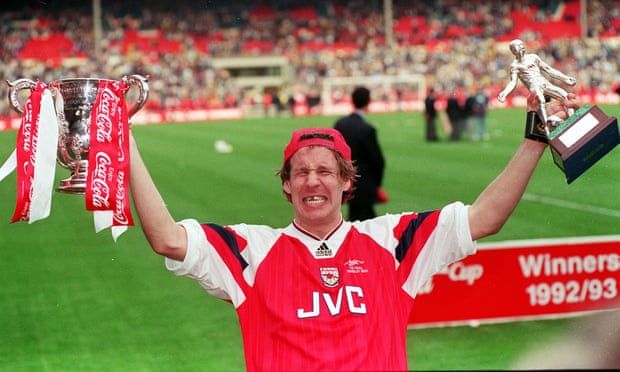

Paul Merson celebrates Arsenal’s Coca-Cola Cup final victory over Sheffield Wednesday at Wembley in 1993.

Paul Merson celebrates Arsenal’s Coca-Cola Cup final victory over Sheffield Wednesday at Wembley in 1993.

“I went out and had the best game of my career. We were 5-0 up and I got a standing ovation from Millwall fans with five minutes to go. Then, in the car park, this 75-year-old geezer comes up to me: ‘I just want to say, Merson, I’ve been coming to the Den 60-odd years and I’ve never seen what I seen today. We’ve never had a standing ovation for an opposition player.’”

Merson pauses as he begins to cry. He shakes his head. “It was…” The words are choked by his tears. He tries again. “It was…” His mouth crumples, and I apologise. “No, don’t worry,” Merson manages to say.

It sounds like he played beautiful football that afternoon? “Yeah,” he says, wiping his eyes. “But the addiction kills you. There should have been more of them good times. I live quite a nice life now but I wouldn’t wish this on anybody in the whole world. It’s a horrible addiction. Even your footballing career, no matter how great it was, passes you by.

“I’ve only got some memories of the really good times. I remember another standing ovation I got at Maine Road with Villa with five minutes to go. But at the time, I’m walking off the pitch like: ‘God, let’s get changed, let’s fucking get going. I want a bet now – or a drink.’ It takes over your life. It’s a hard and draining illness.” Football offered Merson a refuge. “The only time I lived in the moment,” he says, “was playing football.”

In Merson’s raw and sometimes harrowing new book, which is also full of pathos, he describes how he saw space and clarity on the pitch. He compares this ability to a chess prodigy plotting a strategy four or five moves ahead. But in real life he saw little but blurring chaos. He suggests that his brain is “wired differently. It helped me on the pitch. Ask the lads at Arsenal, or anywhere I played. It drove them up the wall. They would complain I was always aiming for the glory ball. It was like my gambling, my drinking, my drugging. It was risk-taking. I didn’t see fear. I could do it and I kept on doing it.

“People talk about being brave on the football pitch. Being brave and clever for me is getting the ball and putting your head up and trying to open up the game. Glenn Hoddle always said: ‘See the picture’. Some players have all the skill in the world, but they can’t see that picture. I could. I’m not saying it happened all the time. I had some shocking games. But I was so much better in football than life.”

Scoring

a penalty for Portsmouth against Millwall in 2003. ‘I remember having

30 grand, in cash, to give to someone after the game’.

Scoring

a penalty for Portsmouth against Millwall in 2003. ‘I remember having

30 grand, in cash, to give to someone after the game’.

His certainty that he is “wired differently” has re-emerged. “They want me to see someone now to get diagnosed with ADHD. I’m 53. This could have been nipped in the bud before, surely? So that scares and frustrates me.”

Merson stresses that his gambling disorder is by far the worst of the three addictions spread across nearly four decades of his life. He was only 16 when he had his first bet as a Youth Training Scheme [YTS] apprentice with Arsenal in 1984.

“I was picking my first wages up on a Friday afternoon. £100. Just finished training, cleaning the boots, the toilets and the bath. I’d never seen a hundred quid in my life. I was counting it and thinking: ‘Oh my God.’ I said to my mate, Wes Reid, who went on to play for Millwall; ‘What are we doing now, Wes?’ I thought he’d say we’d go shopping on Bond Street. He went: ‘I’m going across the road to the betting shop.’ We walked in and it was like stepping onto a spaceship. People roaring and shouting. I lost all my money in no time.

“It was like: ‘Oh God, what do I tell mum and dad?’ I had 21 stops on the tube to think about it. I got to the estate and scraped my face against the wall. I ran in and told my mum I’d been mugged on the train.’ She gave me her digs money.” Merson scrunches up his face. “Every gambler becomes such a good liar. If lying was in the Olympics, gamblers would represent every country.”

There were disturbing times when he considered breaking his fingers with a hammer or slamming a door shut on them so he would no longer be able to call the betting companies. “I was with Villa and we played Charlton away in a night game. I hated night games because I sat in the hotel room all afternoon and gambled. I was constantly ringing up, putting bets on. And then it come into my brain: ‘Break your fingers.’ If you break your fingers, you can’t pick the phone up. People who don’t understand would think that is madness. But this addiction grips you and doesn’t let you go.”

Merson has not had a bet in more than a year but, he says: “This is with me forever. I’m doing all I can to arrest it, one day at a time. But it ain’t going away. If I got to 75 and I still ain’t had a bet, I bet you bottom dollar, if I started betting again it would be worse than last time around.”

Paul Merson says his gambling disorder is by

far the worst of the three addictions spread across nearly four decades

of his life.

Paul Merson says his gambling disorder is by

far the worst of the three addictions spread across nearly four decades

of his life.

He is an amiable and even cheerful man, despite the bleak topic, but Merson feels anger when he considers the gambling industry, “There’s a betting company I used and I looked through my accounts with them. I gave them £135,000 in four months. I rang them up, I emailed them. I said: ‘You let me down. I know you understand I’m a compulsive gambler and you did nothing to stop me.’ They said: ‘No, we’ve looked through the rules and we did nothing wrong.’ But I know hundreds of people have had their accounts shut because they’ve won big.

“I was like a cash machine to them. I was placing a hundred bets a day. All these companies do nothing to stop people with this illness. It hurts me now – at the time it didn’t because I used to hate myself. I saw it as punishment I deserved. But they took full advantage of me and that disgusts me. They fobbed me off: ‘You’re a piece of shit. You’ve gone. We’ve got loads of new ones coming through.’ It’s a conveyor belt of people being destroyed.”

Merson highlights the way gambling advertising is so pervasive – especially around football on television. “It’s so in your face now. People are virtually telling you on the telly you can’t watch football without gambling. Imagine what it triggers in me? Even when I’m driving in the car at seven in the morning and an advert comes on for the prices of a football match in 13 hours’ time, that’s a major trigger. They’ll give the odds on Man United and something in my brain goes: ‘That ain’t bad.’”

Last year, during the first lockdown, Merson spent all his and his wife Kate’s savings in a desolate spree. “At the time I was reading and watching the news a lot and my brain started telling me: ‘We’re not getting out of this. I need to get a future for my wife and three little kids.’ We had a deposit [for a house] and my brain said: ‘You’re not going to be working, there’s not going to be any money coming in. You’ve got to use that money to gamble to make it better.’ I lost everything.”

He has not had a bet since then but he received another jolt last August when his good friends Phil Thompson, Charlie Nicholas and Matt Le Tissier were all axed from Soccer Saturday. Merson and Stelling were retained but they felt the loss deeply. “It’s scary. You think you’ve got this job as long as you don’t do something amazingly silly or get in trouble. I love my job. Ask Kate. Saturday mornings, I’m as happy as Larry. It’s a massive part of my life. I like structure, I like to know what I’m doing. Them lads helped me massively so that was a hard wake-up call.”

While at Aston Villa Merson considered breaking his own fingers so he could no longer call betting companies.

While at Aston Villa Merson considered breaking his own fingers so he could no longer call betting companies.

The old Soccer Saturday gang had made Merson “very comfortable, being dyslexic, on telly. Some footballer names are so long they can’t even get around the shirt. I struggle to say the name and they used to laugh and make me feel at ease. I mess up the names now and everybody goes quiet and it makes me feel thick. I’d rather they were laughing at me in a relaxing way.

“I’m so conscious now that if I mess up a name I think; ‘Oh, you thick…’ because no one’s taking the power out of it by having a laugh. But it’s getting better and I get on so well with new lads like Clinton Morrison. I’m doing OK. So many people worry about yesterday or tomorrow. They miss out on today. I’m trying to live every day and that’s why having a barbecue, going to Homebase, are ordinary things I love. I never did any of that before now.

“About two months ago I’m sitting on the sofa. Kate said: ‘What’s wrong?’ I went: ‘It’s boring. I’m not used to this flat life where everything stays the same. I’ve been on a rollercoaster so long.’ She said: ‘Is this better than down there at the very bottom?’ I said: ‘A hundred times better.’”

Merson’s eyes are gleaming again, with light rather than tears. “I’ve never been able to sit with my feelings until now. I used to push them down with a bet, with whatever. No one ever sat around a table before dinner and asked: ‘How do you feel?’ But now I say to [his young son] Freddie: ‘How do you feel?’ I know he gets a little nervous before playing football. But I say: ‘It’s not a problem. Remember last week? You had them feelings and they passed.’ Same with me, I might get jealous, insecure, sad. That’s my addiction waiting. It’s out there doing press-ups. But I keep myself around people who love me and I keep talking about it. If I keep doing that I can keep it away. I can stay quiet and happy.”