The messages that survived civilisation's collapse

More than 2,000 years ago, in a temple in the city of Borsippa in ancient Mesopotamia, in what is now modern-day Iraq, a student was doing his homework. His name was Nabu-kusurshu, and he was training to be a temple brewer. His duties involved brewing beer for religious offerings, but also, learning to keep administrative records on clay tablets in cuneiform script, and preserving ancient hymns by making copies of worn-out tablets. These daily tasks, and his devotion to beer, writing and knowledge, made him part of an extraordinarily resilient literary legacy.

Cuneiform had already been around for roughly 3,000 years by the time Nabu-kusurshu picked up his reed stylus. It was invented by the Sumerians, who initially used it to record rations of food – and indeed, beer – paid to workers or delivered to temples. Over time, the Sumerian texts became more complex, recording beautiful myths and songs – including one celebrating the goddess of brewing, Ninkasi, and her skilled use of "the fermenting vat, which makes a pleasant sound". When Sumerian gradually slid out of common use, and was replaced by the more modern Akkadian, scribes cleverly wrote long lists of signs in both languages, essentially creating ancient dictionaries, to make sure the wisdom of the oldest tablets would always be understood.

Nabu-kusurshu's generation, who would have spoken Akkadian or maybe Aramaic in everyday life, was among the last to use the cuneiform script. But he probably assumed that he was just one ordinary young writer in a long line of writers, preserving cuneiform for many more generations, under the benevolent eye of Nabu, the god of writing and "scribe of the universe". He faithfully copied the old tablets, noting down for example that a Sumerian sign pronounced "u", could mean marriage gift, burglar, or buttocks. He wrote on the tablets that he copied them "for his own study", perhaps as practice or scholarship, and placed them in the temple as an offering.

"He's learning how to write, and learning these lists, alongside other things, and then dedicating his work to the god Nabu and the temple," says Jay Crisostomo, a professor of ancient Near Eastern civilisations and languages at the University of Michigan, who has studied Nabu-kusurshu's tablets in depth.

It was these humble lists, quietly written in the shadow of a giant ziggurat – a pyramid-shaped stepped temple tower – that would earn Nabu-kusurshu immortality.

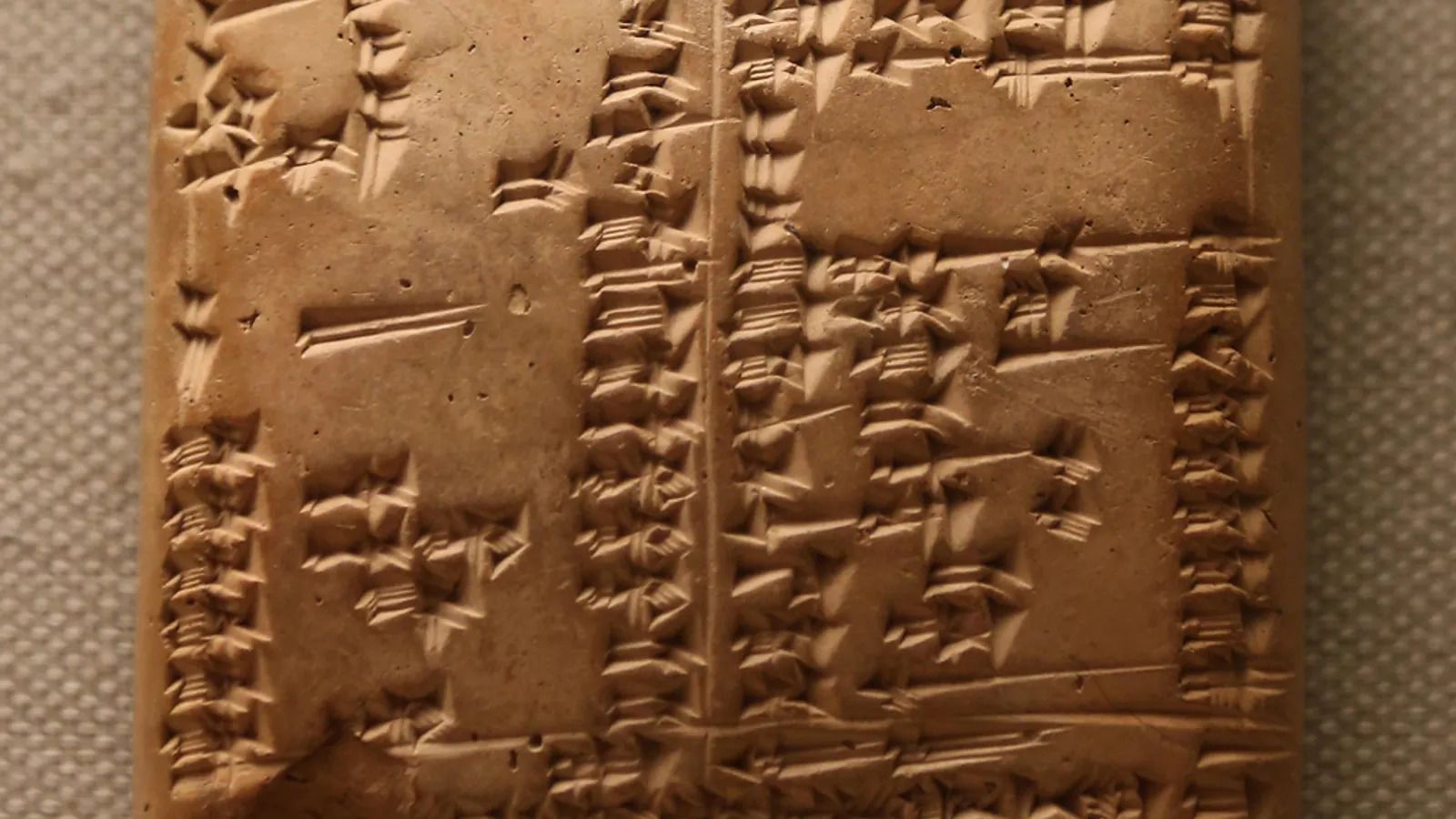

A bilingual cuneiform tablet, listing Sumerian and Akkadian words.

Scribes wrote such lists to ensure that the older Sumerian tablets would

always be understood

A bilingual cuneiform tablet, listing Sumerian and Akkadian words.

Scribes wrote such lists to ensure that the older Sumerian tablets would

always be understood

Many of us may daydream about writing a message that can be read in thousands of years' time, be it to share wonderful poetry with future generations, or warn them about the hazards lurking in nuclear waste.

What's easy to forget is that this is not a mere thought experiment. People have successfully crafted immortal messages – or at least, very long-lasting ones – in the past.

Some of them, like Nabu-kusurshu, even left us a key to entire civilisations.

In the 19th Century, scholars were racing to decipher a mysterious language found on cracked, charred tablets dug up from the sand-covered ruins of Mesopotamian temples and palaces: Sumerian, which had been thoroughly lost and forgotten.

What made the challenge particularly tricky is that Sumerian is not related to any other known language. But the scholars had recently deciphered Akkadian, thanks to its link to surviving languages such as Arabic and Hebrew. And they had also found the ancient scribes' Sumerian-Akkadian clay lists, which they could use as a dictionary.

Among them, one set of tablets stood out for its pristine condition and "distinctive fine script": Nabu-kusurshu's tablets. They were found next to some broken pillars and bricks when archeologists opened the long-buried rooms of the temple at Borsippa around 1880.

"A lot of what we know about Sumerian is via this one man, Nabu-kusurshu," says Crisostomo. He believes the young scribe, who would have been in his late teens or early 20s, produced nearly a quarter of all known copies of a bilingual sign list that proved crucial in the decipherment.

To give you an idea of the size of his impact: these lists helped unlock Sumerian records spanning three millennia of history, including the Sumerians' pioneering use of the wheel, and the 60-minute hour. Altogether, across different languages, there are more than a million cuneiform texts from the ancient Near East – and we can read them thanks to eternal clues left by ordinary scribes like Nabu-kusurshu.

What helped their messages survive, and stay meaningful, over such a long period of time? And how might we use that knowledge to craft our own messages to the future?

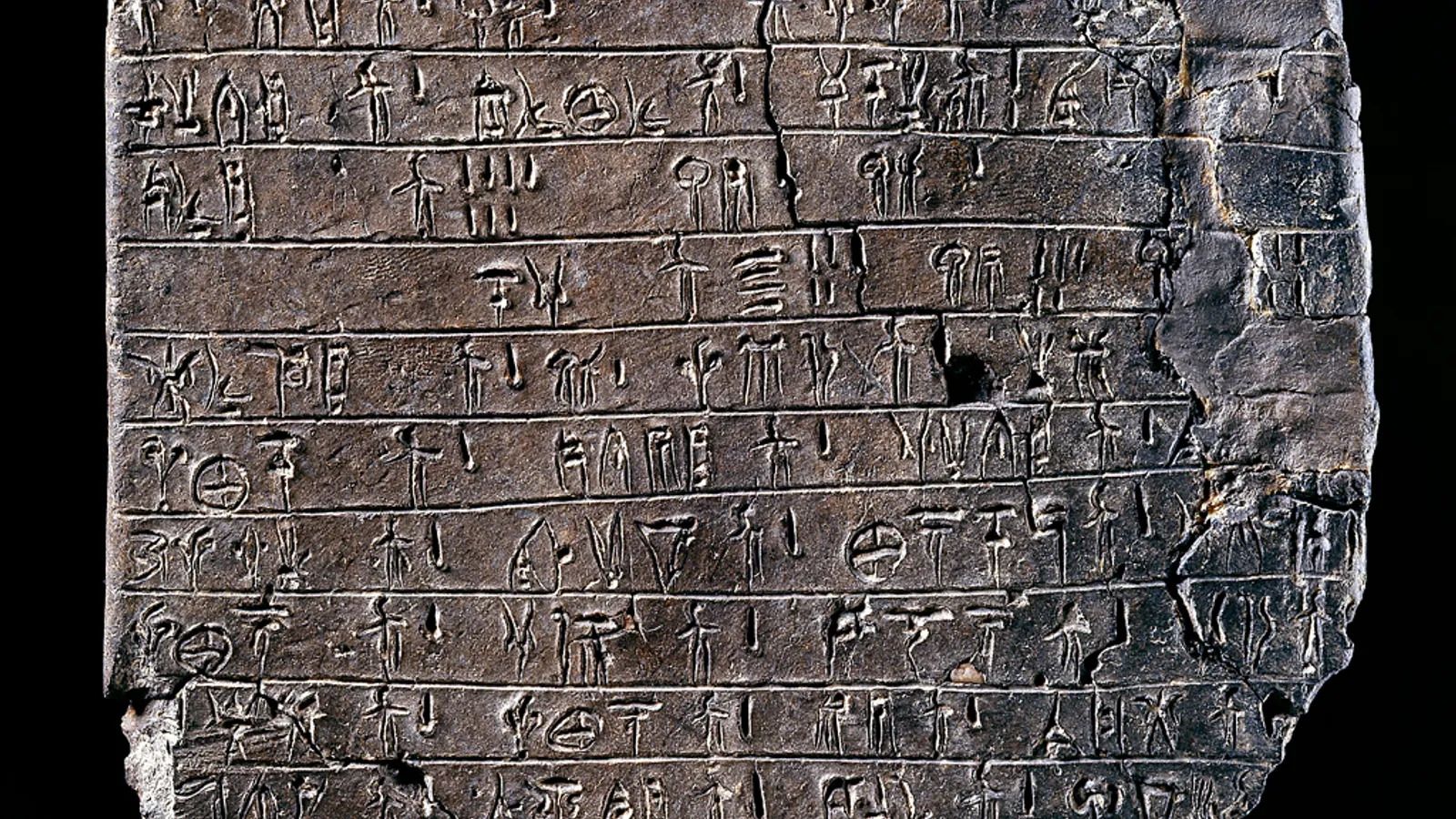

A tablet inscribed with the Linear B script, used on Crete and the Greek mainland before the arrival of the alphabet

A tablet inscribed with the Linear B script, used on Crete and the Greek mainland before the arrival of the alphabet

Most thoughts and ideas expressed by humans barely survive the present moment. History is strewn with references to those that vanished – not just individual messages, but entire languages, and with them, the memories of the societies that spoke them. Who remembers Gutian, a language of ancient Iran? Thousands of years ago, someone gave a Gutian translator a payment of beer, according to a Sumerian clay receipt. And that's pretty much all we know about Gutian. Whatever the Gutian people felt, whatever they wished to tell the world, is lost. All that remains of them are some rather unflattering descriptions by the Sumerians.

On the other hand, there are messages that outlasted centuries of warfare, invasions, and natural disasters. Even though the Spanish destroyed mountains of Maya books, the script survived in rare bark manuscripts and on stone monuments, extending a lifeline to ancient myths and prophecies.

What's the secret of such extrordinary literary longevity? I put that question to three experts on some of on the world's oldest languages and scripts, and also asked them how they would write their own message to the future, based on their insights. All of them mentioned certain material aspects, of course – clay and stone are more durable than paper or digital recording methods. The right climate and environment help with the preservation: cuneiform tablets were in fact often baked and hardened by the fire of burning cities under attack. But the experts' most compelling insights were about the writers themselves.

When talking about writing from the distant past, it can be tempting to portray it as some sort of accidental pile of historical debris. Nabu-kusurshu's legacy, for example, may seem like a fluke of history: the brewer's tablets that turned out to be a kind of Rosetta Stone. But according to the scholars, it's not all due to luck and coincidence. Instead, there are certain habits, values and decisions that may not exactly guarantee literary immortality – but at least, improve its chances.

Of course, the best way to test these factors would be to run a controlled experiment, where different scripts are exposed to challenges – say, the collapse of civilisation – to see which survives. We don't have anything quite like that in history. But we have something that comes a bit close.

In Greece, writing died out after disaster struck the literate elite around 1200 BC – and it was then reintroduced much later

In Greece, writing died out after disaster struck the literate elite around 1200 BC – and it was then reintroduced much laterThe people who forgot how to write

Picture two islands in the Bronze-Age Mediterranean, with sheep peacefully grazing amid olive groves. On both islands, people are busy at work writing on slabs of clay. One island is Cyprus, close to the Near Eastern coast. The other is Crete. On Crete, and on the Greek mainland, an elite called the Mycenaeans are in charge. They write in Greek, using a script called Linear B.

Then, from around 1400BC, disaster strikes the Mycenaeans. First, their palace on Crete is destroyed. Some 200 years later, the palaces on the mainland are also destroyed.

Cyprus is also hit by a catastrophe – historians are still debating what exactly happened. There's some sort of economic collapse, settlements are abandoned, new groups of people arrive from abroad. But even as life changes dramatically, the locals continue to write their script, and experiment with new ones, borrowing techniques from different literate cultures around them.

On Crete and the Greek mainland, however, once the palaces are gone, writing stops. It dies out. Not just Linear B, but also the fundamental knowledge of literacy, just seems to vanish. It's as if an entire society forgets how to write.

This is particularly striking given that Crete was where Europe's oldest scripts evolved, dating back to at least 1800BC. But that fine legacy is wiped out when the Mycenaean elite collapses.

And when people in Greece begin to write again, centuries later, it's in a totally different script, the alphabet, imported from abroad. Their own, older tradition is lost forever.

"In Greece, once you've lost the Mycenaean palaces, there just doesn't seem to be any literacy at all for a while," says Philippa Steele, a senior research associate in classics at the University of Cambridge, and an expert on the ancient scripts of Crete, Cyprus and Greece. "Between 1200 [BC] and around the 8th Century [BC], there's nothing as far as we can tell. While Cyprus remains literate throughout that whole period."

What caused the difference?

We can't say for sure, of course. But Steele believes that it may have to do with how the two communities treated the skill of writing.

Philippa Steele, an expert in ancient scripts at the University of Cambridge, holds her clay tablet with a message to the future

Philippa Steele, an expert in ancient scripts at the University of Cambridge, holds her clay tablet with a message to the futureShared scribbles

On Cyprus, there is abundant archaeological evidence of what Steele calls "reflexes of literacy": scribbles by ordinary people who adapted writing to their own uses, such as merchants marking their pots. This widespread, informal experimenting may have made writing more resilient, she suggests. Even after the destruction and upheaval, and the arrival of new people, the locals on Cyprus held on to their script, and wrote it on little clay figurines that they offered to their gods. Later on, they also wrote different scripts next to each other, for example pairing their own Cypriot syllabic script with Phoenician – which eventually made decipherment easier.

But on Crete and the Greek mainland, Linear B never seeped out into the wider society, judging by the archaeological finds, Steele says. The Mycenaean scribes were anonymous, and their art was not particularly celebrated. "There are just zero depictions of people writing, and zero depictions of things that were involved in writing."

Nor were there giant Linear B texts written across rock faces or palace walls, which might have reminded people that there was this valuable skill called writing. Instead, Linear B led a hidden life inside the palaces. And when the palaces fell, it had no other niche where it could survive. As Steele concludes: "If literacy is restricted, it might be easier for a writing system to die out if its context of use disappears." These insights from the past may help us solve pressing problems in the present, she argues, such as saving modern-day endangered writing systems.

Linear B did have a second life, however. It took scholars a long time to decipher it, because it was not written alongside any surviving scripts. But they eventually succeeded in the 1950s, and today, much of it can be read.

The message should be multilingual, so there is a better chance for at least one of the languages to still be spoken in the distant future – Philippa Steele

I ask Steele how she would write an immortal message. She gets back to me not only with an answer, but with an actual message, in tablet form.

It is made of clay, for durability, "which should ideally be fired", though she used air-dried modelling clay. It is multilingual, "so there is a better chance for at least one of the languages to still be spoken in the distant future – plus a multilingual message gives more clues for future decipherers than a monolingual message would". (Multilingual means several languages written side by side, as in the Rosetta Stone, or Nabu-kusurshu's tablets).

She chose a simple message: "My name is Pippa Steele and I wrote this in Cambridge in the year 2022."

With the help of friends, she wrote it in English, Spanish, Chinese and Arabic, since those are widely spoken languages globally, and are also all well-represented locally: "I could of course have added many others."

Mayan hieroglyphics in Palenque, Mexico

Mayan hieroglyphics in Palenque, Mexico The Maya messages that want to be read

One lesson from ancient Crete and Cyprus might be that to write an everlasting message, it's a good idea to start with ensuring people can make sense of it in the present.

As those working in decipherment often point out, that was the original purpose of most scribes: to communicate. Ancient civilisations usually didn't intend to create an un-crackable code, quite the contrary.

"A code exists so it stays secret and can only be read by certain groups," says Christian Prager, an expert on classic Mayan at Bonn University and part of a team compiling an online database and dictionary of the script. "With the Maya script, which was so publicly present on stelae [big inscribed stone pillars] and buildings, it's the opposite. It was there to be understood."

The Maya script was used for about 2,000 years, and Maya languages are still spoken in Mexico, Belize, Guatemala and Honduras. The earliest hieroglyphs date to about 250BC. People continued to write the script in secret even after the Spanish conquest, into the late 17th Century AD. Today, about 60% of the hieroglyphs are deciphered, enough to understand the gist of all the texts, Prager says.

Within three days, you can read the Maya script – Christian Prager

While the work on each sign can be slow and painstaking, modern scholars are assisted by long-dead Maya scribes, who added little markers to their signs to give a clue to their meaning. Recently, one of these markers – the one for "stone" – helped Prager and his colleagues figure out the sign for "pecking a new stela". The link to living Maya languages has also played a huge part in the decipherment.

Even though only a few people in the Maya world knew how to write, Prager believes a relatively wide range of people would have been able to grasp basic messages, such as a portrait of a king and his name displayed on a stela in a market square: "I am sure they were able to say, this is the name of the king. Because when we teach courses in the Maya script today, within three days, you can read the Maya script. Maybe not the fine linguistic details, but you can recognise sequences of signs."

Carving your name on a big stone, ideally next to a self-portrait, seems to be a truly timeless, enduringly meaningful format, not just in the Maya world: king's names and the word "king" are often the first to be figured out in undeciphered scripts.

A 12th-Century Maya manuscript housed at the Saxon State Library in Dresden, Germany

A 12th-Century Maya manuscript housed at the Saxon State Library in Dresden, GermanyA living organism

The Maya script may not just be figuratively immortal, but literally so. For the Maya, it had a life of its own.

"The script was an organism in itself," Prager says. "You can see it when you look at the hieroglyphs, there is something animated about them. The classic Maya saw many everyday objects as animated, including their script. Stelae were given individual names – that says a lot about how they were valued, and how much they were, and are, part of the culture." When a stela was no longer used, it was given funerary rites.

These deeper beliefs have some useful practical consequences when it comes to reading classic Mayan today. Maya scribes kept the shape of the signs exactly the same from the earliest stone inscriptions to the last bark books, for example. It probably had to do with the scribes' desire "to use an unchanged writing system, just like their ancestors," Prager says. "It's astonishing, it's something you very rarely find [among ancient scripts]." Rather handily, it means that once you know the script, you can read Maya documents from all these different time periods.

When I later ask Prager how he would write a message so that it can be read in thousands of years time, Prager responds with a Maya level of scale and ambition: "The message would have to be monumental and made of stone, to withstand the wind, weather and humans!"

The Great Wall of China is the best example of an everlasting message, he says – even at the time it was built, it showed enemies the borders of the Chinese realm, and the political and economic power of those who built it.

For his own message, he envisages "landscape-spanning, monumental buildings that can't be erased", inscribed with a text in all modern and ancient languages that is set into the mega-building every 100 metres. "One of those messages will outlast future catastrophes," he concludes.

A Neo-Assyrian relief of a man from Nimrud, northern Mesopotamia

A Neo-Assyrian relief of a man from Nimrud, northern MesopotamiaThe brewer's list

By the time Nabu-kusurshu, the young brewer of Borsippa, was working on his lists around 450BC, many of the languages that had once filled the Near East had already vanished, including once-mighty languages like Hurrian and Hittite. Amorite, spoken by powerful nomad-kings in ancient Syria, and mentioned in ancient letters as a highly useful language to learn, disappeared with barely a written trace.

And yet, Sumerian – arguably the most impractical of them all, once it had fallen out of daily use – lived on and on. From about 2000BC, "nobody spoke Sumerian, but they were still writing it. And that's part of my extreme fascination with this," says Crisostomo. "What made it continue?"

The answer may lie in those very first cuneiform signs, pressed into clay by the Sumerians. From the start, writing was associated with the Sumerians, Crisostomo says. Over time, it kept that association with an ancient culture and its gods, cities and legends, and with the power that came with that.

King after king used that association to legitimise their own rule, even if they had no Sumerian ancestry themselves. They composed Sumerian songs predicting their words would be treasured by people "in the distant future". By collecting tablets, boasting of their Sumerian knowledge, commissioning scribes, or being portrayed with a stylus in their belt, they too became part of that immortal lineage.

"It's about claiming authority that goes all the way back to the beginnings of writing, and the beginnings of knowledge," says Crisostomo.

Young Iraqis play soccer in the shadow of the ruins of a ziggurat in Borsippa, Iraq

Young Iraqis play soccer in the shadow of the ruins of a ziggurat in Borsippa, Iraq

That literary heritage ranged high and low, and included hymns and omens, but also, very old drinking songs. As in the Maya world, the link between writing and power was advertised through monumental inscriptions. Nabu-kusurshu's tablets were sustained and protected by an entire culture.

But there was, perhaps, also an element of individual choice. Nabu-kusurshu appears to have taken pride in his writing, and taken care to perfect it, given how exceptionally neat it was.

Crisostomo is scouring the world's museums for more of Nabu-kusurshu's tablets, of which about 24 have been found. He has studied every detail of the brewer's handwriting, from how he shaped his signs to how he spaced his lines. "It's things like that where you start to really feel like you know these people."

Despite his own love for written language, Crisostomo says his message for the future would probably be an image – so that "it could transcend the need for language", and avoid the pitfalls of decipherment.

It appears, then, that a good rule of thumb is to make your message to the future either gargantuan enough that it can't be ignored, or so small that it slips through history almost unnoticed, perhaps protected by its low profile. A visual or contextual cue seems to help, be it by adding a picture, or placing it somewhere relevant to its meaning – like a temple or monument. And the scholars appeared to find it obvious that it was better to use an existing language, than try to make up an artificial, future-proof one. After all, real languages have cultures to love and support them, providing future decipherers with a wealth of clues and meaning.

In fact, cuneiform is experiencing a renaissance these days, as a young generation of Iraqis learn and experiment with it. A similar spirit is infusing the Maya hieroglyphs with new life. Native Maya speakers use it to make art, and put up new stelae to commemorate important events.

That human connection and fellowship, across vast stretches of time, perhaps forms the final step for an immortal message. As much effort as we may put into it, we can only trust that at the other end of the line, there'll be another person hearing our faint voice, and caring enough to listen.

Crisostomo often remembers this when he works on ancient tablets, some marked by thumb-prints of long-dead scribes. "Sometimes you'll sit there and you put your thumb right in that same space, and you think, 'OK, maybe this person was holding this tablet just like this, 4,000 years ago, and they're holding it and they're writing it, and I'm sitting here, reading what they wrote.'"