Why your life could be part of someone else's game

Is the world controlled by a secret cabal of deep state operatives? Is "science" merely a front for a fantastically complex war on freedom? Such false claims are made by movements like QAnon, which since 2017 has grown from a far-right cult into a viral phenomenon. I'll spare you the more lurid details about the lies they spread – not least because, according to research by media scholars like Whitney Phillips, doing so could inadvertently help to amplify conspiracies. But you may be both alarmed and intrigued to learn that as many as 15% of Americans agree with QAnon's falsities.

How can so many people believe such improbable, paranoid fictions? Part of the answer is precisely that these beliefs are so alarming and intriguing. But it's also something more than that. Journeying into their mirror-world is akin to playing a uniquely compelling 21st-Century game: one offering a heady mix of purpose, exceptionalism and escape in its pursuit of purportedly forbidden knowledge through the internet's rabbit-holes.

We live in a world that "increasingly feels like a game we can't stop playing"

I owe this analogy to Adrian Hon, a game designer and author of a new book called You've Been Played, which explores the increasingly uneasy ways in which game-like elements permeate our digital age. In his book, Hon charts the similarities between games and contemporary conspiracy theories – and much more. Game-like elements, he argues, underpin countless aspects of our lives today, from the mechanics of the workplace to how we spend our leisure time. You may consider yourself immune to conspiratorial manipulations. But, as the title of Hon's book suggests, you are most assuredly being played elsewhere. And – contrary to the fantasies of QAnon's would-be freedom fighters – there's no easy way to take back control.

I first met Hon in 2006, when he was the producer and lead designer for one of the world's most popular Alternate Reality Games (ARGs), Perplex City. An ARG is a fiction that plays out across multiple media, driven by a community of players encouraged to research puzzles and clues scattered across seemingly unrelated sources. Secret web addresses may be seeded in billboards, online videos or forum posts. Messages from – or even conversations with – fictional characters, played by actors, further the story. An active community of players and wiki-style repositories track everything that happens in the "alternate" reality while, behind the scenes, authors and designers drip-feed their players new material and challenges.

Materials from Perplex City, an Alternate Reality Game created in the 2000s

Materials from Perplex City, an Alternate Reality Game created in the 2000s

I spoke to Hon again earlier this year, and we discussed the parallels between ARG games and conspiracy theories. QAnon is, we agreed, far more sinister and alarming than any game. Its potency is interwoven with matters of faith, politics and prejudice. Yet the ways in which its online transmission has tapped into a crisis of trust, while filling that void with a participatory fantasy, is painfully symptomatic of larger ills – and of the ways in which people desperate for pleasure, purpose and community can get caught up in unreal versions of the world.

In the case of Perplex City – for which, back in 2007, I designed several of the collectible puzzle cards that were sold to fund the game – the prize was participation in a rich and multifaceted story, woven throughout everyday life. In the case of QAnon, the prize is not so much piecing together fictions as claiming you've seen beneath reality's surface into a hidden pattern: one able to explain away inconvenient facts, while justifying everything from shooting up pizza parlours to storming the US Capitol.

As Hon puts it, anyone hoping to confront the toxic appeal exerted by modern misinformation needs to face the fact that – among other things – people join the communities promulgating it because "they find it fun, they find it engaging, they feel valued". And the same mechanics underpinning this captivation are at work among not millions but billions of people every day, in the algorithmically-honed arenas of social media and weaponised information: in a world that "increasingly feels like a game we can't stop playing".

Worker play

You don't have to believe in conspiracy theories to be part of this game. If you have ever worked in one of Amazon's Fulfilment Centres, as the company likes to call its warehouses, you may have come across the game-like experiences that it uses to incentivise employees. One former warehouse worker, Postyn Smith, described in a 2019 Medium post the kind of "FC Games" on display in stowing and picking stations: competitive scenarios such as one-on-one dragon races between nearby workers, with the dragons' speed defined by employees' work rates, or races between Amazon mascots around a virtual race course. More elaborately, one game features a kind of "gamified feudalism" in which workers are "literally serfs helping to mine the quarries and build the castle": labourers creating day-by-day a miniature medieval world.

A warehouse worker dispatches a gaming console

A warehouse worker dispatches a gaming console

On the one hand, a benign account of such "gamification" is that it makes drudgery a little more endurable. On the other hand, as Hon notes, games designed to encourage workers to work harder, faster and for longer at fundamentally disengaging work are at best a temporary distraction – and at worst a none-too-subtle form of surveillance and coercion. As he puts it, "there's another way to describe workers labouring longer for the same pay: it's called cutting their wages".

The word "gamification" is a curious one. Superficially, its meaning is clear enough. To gamify something is to make it like a game, usually by wrapping game-like elements around it: points, missions, in-game rewards; a profile, avatar or fantastical environment. By doing this, the thinking goes, the activity in question is made more engaging and enjoyable. Everyone is a winner! Yet the very essence of a game is that it's voluntarily undertaken, and that it confers satisfaction through a mixture of luck, skill and meaningful choice. None of these things are much in evidence in the context of an Amazon warehouse, no matter how many virtual dragon races take place within it.

None of these quests and bonuses and promotions would matter if gig economy workers' overall pay wasn't so low

The same is true of the "quests" (also known as "opportunities") that Uber offers its riders for "reaching certain trip goals in a set amount of time", and the "bonuses" Lyft awards drivers who achieve targets like "streaks" of back-to-back accepted requests. Or the incentives that delivery companies like Instacart, Postmates and Shipt offer for completing a minimum number of weekly jobs. As Hon notes, "none of these quests and bonuses and promotions would matter if gig economy workers' overall pay wasn't so low." As it is, however, bonuses of a few extra dollars "offered to you multiple times a day could make up a substantial proportion of your income", at which point they effectively cease to be optional. The system's shifting and ceaselessly monitored targets are, in effect, an intangible and unaccountable level of management.

In a sense, gamification of this type – surveillance-driven, offering only a simulacrum of choice – is both the opposite of QAnon's sprawling enticements and a source of the purposelessness it preys upon. The more your work resembles a rigged game you have no choice but to play, the more likely you are to seek meaning and community elsewhere, and the more likely it may seem that hidden manipulations lurk behind all public rhetoric. "Companies that treat their workers like the robots they wish to replace them with," Hon argues, "also motivate workers by telling them they're part of a greater mission." But there's nothing authentic about most of the opportunities, incentives and targets on offer. They are, in the words of the academic and game designer Ian Bogost, pure "exploitationware": software loops whose ultimate purpose is to extract the maximum possible value at the minimum possible cost.

Gamification underpins many fitness regimes

Gamification underpins many fitness regimes

It's not all gig work and covert coercion in the realm of gamification, of course. If you've ever used a fitness app, liked a post on social media or found yourself adding information to a profile in order to achieve "completion", you've participated in some of the planet's most commonly gamified interactions. And your actions are likely to have been converted into data that will, over time, be used to further calibrate your own and others' incentives, to better engage you in whatever activity the software is promoting: running, cycling, weighing yourself, sharing images, offering verdicts on others' opinions, feeding saleable information into a database.

The philosophy underlying this is known as behaviourism, and it's based on a deceptively simple proposition. Rather than trying to understand the inner intricacies of people's mental states, behaviourism suggests that paying close enough attention to stimuli and responses – that is, to the inputs and outputs of the black box known as "you" – is sufficient for understanding the human animal. Once established, this understanding can then be used to optimise both people and the systems surrounding them. A rat in a cage will learn, over time, to associate pulling a particular lever with food, or a particular stimulus with pain. Similarly, a human presented with a sufficiently finely-honed feedback loop – in which, for example, scrolling an ad-packed feed is rewarded by endless screenfuls of videos – will be trained into a predictable behavioural pattern. And the same applies to everything from visiting the gym to brushing your teeth, or from hitting a productivity target to re-ordering a product. If a behaviour can be tracked and rewarded, people can in principle be trained to do more of it.

If you've ever found yourself nudged towards just one more click on social media – or to hit a target of daily steps or virtual quests – you'll have felt the force of these incentives

At root, then, gamification can be thought of as an apparatus of feedback loops intended to reinforce certain behaviours, and, by extension, as an expression of faith in behaviourist models of mind and body. If you've ever found yourself nudged towards just one more click on social media – or to hit a target of daily steps or virtual quests – you'll have felt the force of these incentives. And you may well have been grateful for them.

If you're aching to acquire online clout, then an ecosystem of mutually reinforcing engagements offers an endlessly enticing proposition. If you're trying to get fitter or lose weight, it can be both useful and motivating to break the task down into a series of targets, incentives and progress rewards. What is a game or a sport, after all, if not a structure within which luck and skill can endlessly be reified and rewarded?

Feedback loops can trap us in gamified habits

Feedback loops can trap us in gamified habits

Technology's transformation of sprawling aspirations into manageable, measurable elements was the subject of a TED talk I gave in 2010, inspired by games like World of Warcraft and the power of the progression systems within them. I was, and continue to be, in awe of games' ability to motivate and enthral us. As I was slow to realise, however, there's all the difference in the world between being helped to pursue a meaningful goal – whether it's health, pleasure or productivity – and being presented with various forms of optimisation and box-ticking as if these were themselves the height of human aspiration.

"There's something," Hon told me, "that I wish I'd put in the book, which is the reason why a rat in a cage pushes a lever so much. It's because it's in a cage. It doesn't have anything else to do." Behaviourism offers an excellent description of how animals constrained within certain systems will respond to certain incentives. As a long-term recipe for human thriving, however, it's fatally undermined by its self-fulfilling over-simplifications: by the ways in which it suggests meaningful choices are bugs to be ironed out of suboptimal systems, rather than central aspects of freedom and dignity.

The reason why a rat in a cage pushes a lever so much? It's because it's in a cage

"Whenever people say to me, ‘hey, we're good, we made this thing fun!'" Hon continued, "I think, 'well, would your users really be doing this if they could do something else?' We see this not just with work, but also with consumer gamification, meditation apps, whatever… a solution is being presented to people as something that clearly works, because people do it. But if you were to promote the idea of having a nice walk rather than using a meditation or brain training app, say, that would probably be a better solution for most people. And it would be cheaper. But of course you can't make any money like that."

The lesson the best games teach, in other words, is precisely the opposite of the one implied by most gamification. A rat pressing a lever 500 times isn't telling you how much fun it's having. It's expressing the fact that, out of the meagre options on display, this is the least terrible. Similarly, working with the grain of human nature doesn't mean trying to make people as predictable or optimisable as machines. It means taking a deep interest in why we love to play, for its own sake – then exploring how this might transform everyday experience without either deceiving or diminishing us.

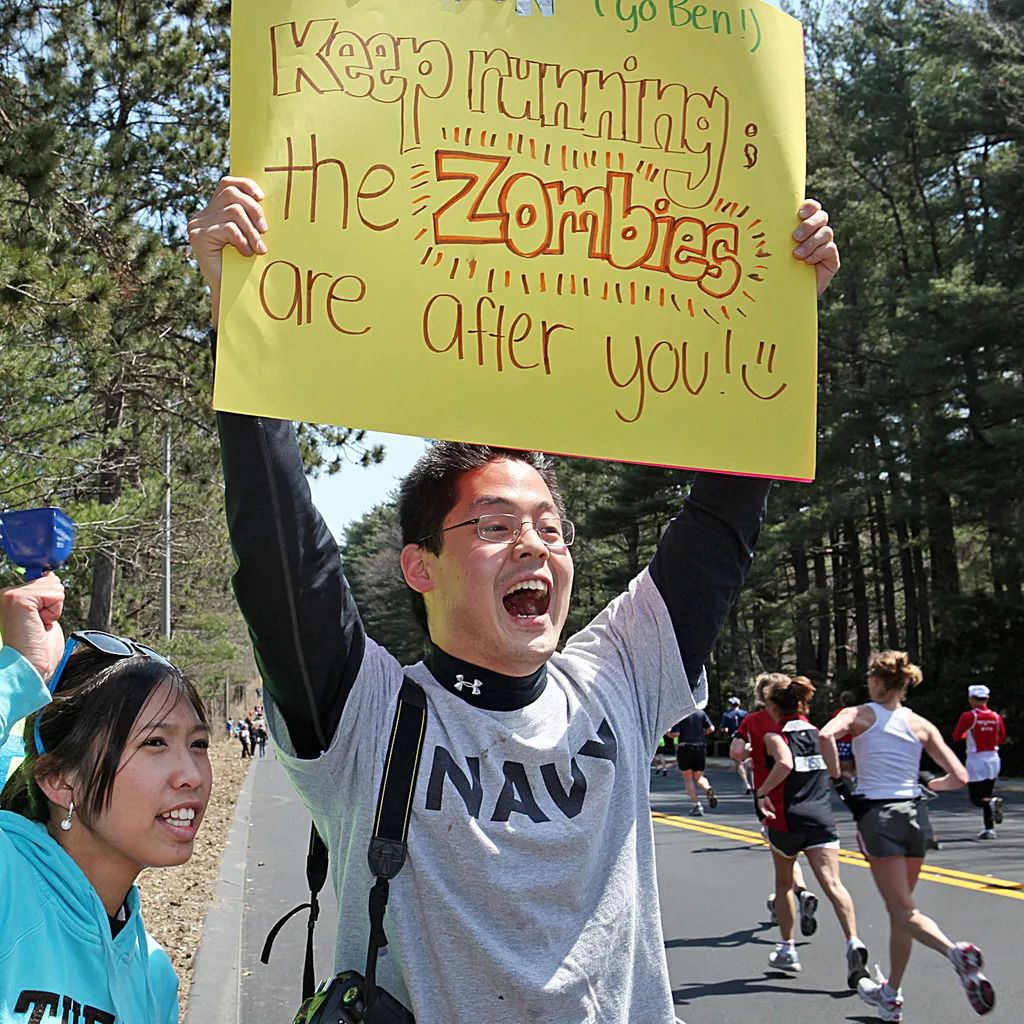

If the app "Zombies Run!" was a person...

If the app "Zombies Run!" was a person...

Today, Hon is both a passionate advocate for video games as a medium and the designer of the world's most popular smartphone fitness game. The game is called Zombies, Run! and Hon co-created it in 2012 with the author Naomi Alderman, who also served as lead writer for Perplex City. As the name suggests, it's a running game with a difference, the difference being that it asks you to imagine you're in a post-apocalyptic world fleeing brain-eating hordes of the undead. This may sound off-puttingly intense, but one key to its success is the degree to which it trusts players' imaginations – and, rather than pushing badges and targets into their faces, takes a deep interest in enhancing the actual, everyday experience of going for a run.

"When I'm out there, sweating, especially if I'm a beginner, I don't want to get a badge after I finish," Hon explained when I asked him about the game's origins. "I'm not interested in seeing a map of the territory after my run. That sucks. I want to transform the ordinary experience of this activity. That's why the game is basically audio, and why it has a story. Because otherwise it's going to disrupt the activity without doing anything to transform it." At the heart of Zombies, Run!, in other words, there beats a lovingly crafted audio drama (having an internationally bestselling, award-winning author as its co-creator helps with this). And while every aspect of the game is built around the act of running, it remains – crucially – entirely relaxed about how far, fast and often you do so.

No one should have to endure nagging and shaming by their apps just because designers are being driven to increase user engagement by any means possible

You can, of course, choose to track your progress and aim for certain targets – and plenty of the game's 10 million players do so. But these elements are optional, and their gamification elements transparent. "Gamification should not be on by default," Hon writes in the last chapter of You've Been Played, which sets out his vision for doing it well (in every sense). "No one should have to endure nagging and shaming by their apps just because designers are being driven to increase user engagement by any means possible." If the experience you're offering is truly as compelling and transformative as you claim, you should have enough faith in it to make lever-pushing and target-hitting optional. Otherwise, you're not so much enhancing someone's life as trying to trap them in a cage.

What else does the responsible use of gamification entail? It's hard for any software – or workplace, or society – to operate ethically if too great a power imbalance is embedded within it. What this means, for Hon, is that "if there is a knowledge asymmetry between a user and designer – for example, if the designer hasn't adequately disclosed how a gamified app works or provided good evidence for its efficacy – then people can be misled into using services they wouldn't have done otherwise." Transparency and the principled rejection of over-claiming are key. Similarly, "outsized rewards and punishments are an eye-catching way to motivate us, but they warp people's reasons for participating… and they can lead them to harmful or unhealthy behaviour".

Zombies, Run! does reward players with "supplies" during a run that can be spent on improvements to their home base afterwards; and some of these supplies are lost if they're caught during a zombie chase. But it takes only a few minutes to replace this loss, while the entire "chase" mechanic can, if a player wants, be turned off without incurring any penalty. Helping people access and enhance the intrinsic pleasures of running – its freedom, its simplicity and inclusiveness, its potentials for thought and escape – is the ultimate prize.

The final point Hon makes in You've Been Played is also the most important: you need to work on behalf of users. If you're a software designer, this means asking what is it your software is actually encouraging people to do – and why they might wish to do so. So far as the rhetoric of software design is concerned, of course, almost every company will argue that they're trying to improve users' lives. But, Hon notes, "it's easy for designers to blind themselves to the reality of what they've made." Consider the casino-like loops of Candy Crush Saga, or countless other mobile games. If players find them compelling, who are we to deny them their pleasure? One answer, uncomfortable though it may be, is that practising ethical design means considering not only what people can be made to want at a particular point in time, but also what they're likely to regret in the long run – not to mention the opportunities they'll have missed by the time they quit.

Sometimes, games can become treadmills that would be better avoided

Sometimes, games can become treadmills that would be better avoided

Like Hon, I have poured tens of thousands of hours into video games across the course of my life; and many of these experiences have been deeply satisfying, moving, entertaining or delightful. But I also found myself nodding along when reading his description of the hundreds of hours he has spent on gamified treadmills which were, "in retrospect, a complete waste of my time. My life would have been better had I never touched them."

"Even at the time, I knew there were better ways for me to relax, like reading books or playing more interesting games, but those experiences weren't designed with the same compulsion loops that kept me coming back… and I'm a game designer, so I ought to know better," he writes.

Despite – or, perhaps, because of – all this, Hon still considers himself an optimist. "I'm amazed at the tools at our disposal to change the world," he told me towards the end of our conversation. "I know people are able to do amazing things, if you find the right combination of conditions and environment, of rights and guides. Gamification can work. But it can't just be like, here's five points for taking part in democracy. You can use game design to help people talk to other people from different viewpoints. You can make them feel safe while doing it, make participation better, have a better interface. At the moment, when we go online to take part in certain aspects of our society, the experience just sucks." Here, as in countless other areas, good design can elevate as well as manipulate human decision-making. It can gift our bottomless capacity for play better outlets than a "like" button – but only if the will exists to do so.

Ultimately, as is often the case with technology, the most significant questions are those that some people would rather never get asked. What underlying purposes do the incentives built into particular systems and tools serve? What might it mean to align these with objectives other than power or profit? The best games, Hon believes, "are patient and forgiving teachers, allowing players to experiment and improvise, and when they're ready, helping them to soar". They are paths leading towards something beyond the game: tools of possibility rather than coercion. And, for all its hazards, gamification too can be a part of this. Just so long as its levers and loops aren't mistaken for a final verdict on human nature – or the roadmap for a future within which work, play and consumption are equal grist to behaviourist mills.