The crazy plan to explode a nuclear bomb on the Moon

The moment astronaut Neil Armstrong stepped out on to the Moon's surface in 1969 is one of the most memorable moments in history.

But what if the Moon Armstrong stepped onto was scarred by huge craters and poisoned from the effects of nuclear bombardment?

At first reading, the title of the research paper – A Study of Lunar Research Flights, Vol 1 – sounds blandly bureaucratic and peaceful. The kind of paper easy to ignore. And that was probably the point.

Glance at the cover, however, and things look a little different.

Emblazoned in the centre is a shield depicting an atom, a nuclear bomb, and a mushroom cloud – the emblem of the Air Force Special Weapons Center at Kirtland Air Force Base, New Mexico, which played a key role in the development and testing of nuclear weapons.

Down at the bottom is the author's name: L Reiffel, or Leonard Reiffel, one of America's leading nuclear physicists. He worked with Enrico Fermi, the creator of the world's first nuclear reactor who is known as the "architect of the nuclear bomb".

Project A119, as it was known, was a top-secret proposal to detonate a hydrogen bomb on the Moon. Hydrogen bombs were vastly more destructive than the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima in 1945, and the latest in nuclear weapon design at the time. Asked to "fast track" the project by senior officers in the Air Force, Reiffel produced many reports between May 1958 and January 1959 on the feasibility of the plan.

The US was concerned that Soviet missile technology was advancing faster than they could keep up

The US was concerned that Soviet missile technology was advancing faster than they could keep up

Incredibly, one scientist enabling this horrific scheme was future visionary Carl Sagan. In fact, the existence of the project was only discovered in the 1990s because Sagan had mentioned it on an application to an elite university.

While it might have helped to answer some rudimentary scientific questions about the Moon, Project A119's primary purpose was as a show of force. The bomb would explode on the appropriately named Terminator Line – the border between the light and dark side of the Moon – to create a bright flash of light that anyone, but particularly anyone in the Kremlin, could see with the naked eye. The absence of an atmosphere meant there wouldn't be a mushroom cloud.

There is only one convincing explanation for proposing such a horrendous plan – and the motivation for it lies somewhere between insecurity and desperation.

It didn't help American nerves that Sputnik was launched on top of a Soviet intercontinental ballistic missile

In the 1950s, it didn't look like America was winning the Cold War. Political and popular opinion in the United States held that the Soviet Union was ahead in the growth of its nuclear arsenal, particularly in the development, and number, of nuclear bombers ("the bomber gap") and nuclear missiles ("the missile gap").

In 1952, the US had exploded the first hydrogen bomb. Three years later the Soviets shocked Washington by exploding their own. In 1957 they went one better, stealing a lead in the space race with the launch of Sputnik 1, the first artificial satellite in orbit around the world.

It didn't help American nerves that Sputnik was launched on top of a Soviet intercontinental ballistic missile – albeit a modified one – nor that the US's own attempt to launch an "artificial moon" ended in a huge, fiery explosion. The inferno that consumed their Vanguard rocket was captured on film and shown around the world. A British newsreel at the time was brutal: "THE VANGUARD FAILS…a big setback indeed…in the realm of prestige and propaganda..."

The successful launch of Sputnik in 1957 caused consternation in the West

The successful launch of Sputnik in 1957 caused consternation in the West

All the while, US schoolchildren were being shown the famous "Duck and Cover" information film, in which Bert the animated turtle helps teach children what to do in the event of a nuclear attack.

Later that same year, US newspapers citing a senior intelligence source reported that "Soviets to H-Bomb Moon On Revolution Anniversary Nov 7" (The Daily Times, New Philadelphia, Ohio) and then followed it up with reports that the Soviets might already be planning to launch a nuclear-armed rocket at our nearest neighbour.

Like with other Cold War rumours, its origins are hard to fathom.

Strangely, this scare also likely motivated the Soviets to develop their plans. Codenamed E4, their plan was a carbon copy of the Americans', and eventually dismissed by the Soviets for similar reasons – the fear that a failed launch could result in the bomb dropping down on Soviet soil. They described the potential for a "highly undesirable international incident".

They may have simply realised that landing on the Moon was the bigger prize.

But Project A119 would have worked.

In 2000 Reiffel had his say. He confirmed that it was "technically feasible", and that the explosion would have been visible on Earth.

The loss of the pristine lunar environment was less of a worry to the US Air Force despite the scientists' concerns.

"Project A119 was one of several ideas that were floated for an exciting response to Sputnik," says Alex Wellerstein, a historian of science and nuclear technology, "that included shooting down Sputnik, which feels very spiteful. They refer to them as stunts… designed to impress people.

"Now what they did in the end was put up their own satellite, and that took a little while, but they continued this project somewhat seriously, into at least the late 1950s.

"It is a pretty interesting window into the sort of American mindset at that time. This push to compete in a way that creates something very impressive. I think, in this case, impressive and horrifying are a bit too close to each other."

He isn't sure that fear of the anti-communist witch hunt made nuclear physicists work on this project. "Anyone who's in these roles is probably self-selected to some degree," he says. "They don't mind doing the work. If they were afraid, they could do a million other things. A lot of scientists did this in the Cold War; they said physics has gotten too political."

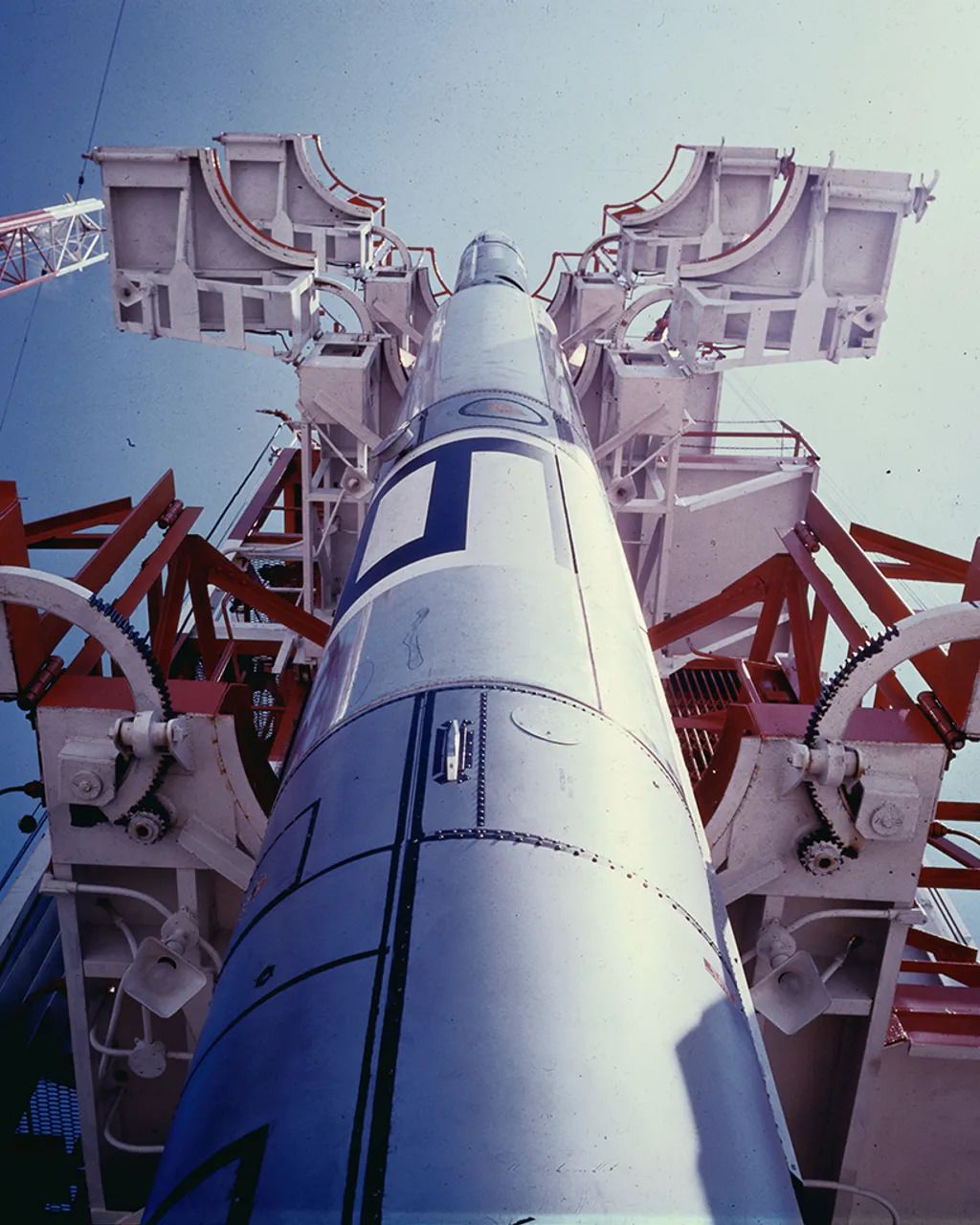

The US attempt to send a satellite into space in 1957 failed when the Vanguard rocket exploded on launch

The US attempt to send a satellite into space in 1957 failed when the Vanguard rocket exploded on launch

There may have been more self-examination by the Vietnam War.

"Project A119 reminds me of the segment in The Simpsons when Lisa sees Nelson's 'Nuke the Whales' poster on his wall," says Bleddyn Bowen, an expert in international relations in outer space. "And he says, 'Well you've got to nuke something.'

If some of the more outlandish ideas don't find root in the US, that doesn't mean that they couldn't find favour further afield

"These were serious studies, but they didn't get any serious funding or attention when they left the space community. It was part of the late 50s, early 60s space mania before anybody knew exactly what nature the Space Age was going to take," he says.

"If there is going to be anything resembling this kind of lunar hysteria again it is going to run afoul of the established international legal order… agreed by almost every state in the world."

Could these plans surface again, despite the international consensus? "I've heard some noises coming out from some places and the Pentagon about looking at US Space Force missions for the lunar environment," Bowen says.

If some of the more outlandish ideas don't find root in the US, that doesn't mean that they couldn't find favour further afield – such as China. "I wouldn't be surprised if there's a community in China now wanting to push some of these ideas because they think the Moon is cool, and they work in the military," Bowen adds.

Most of the details of Project A119 are still shrouded in mystery. Many of the were apparently destroyed.

Its ultimate lesson, perhaps, is that we should never gloss over the research paper with the blandly bureaucratic name without, at least, reading it first.