The ‘Global Britain’ Conundrum

As Boris Johnson prepares to host Joe Biden and the leaders of the world’s other G7 democracies this weekend, Britain appears to have recovered something of its old self. After years of stasis, slump, and division culminating in last year’s catastrophic COVID-19 response, the country can legitimately count itself in a vanguard of powers leading the globe out of the pandemic.

And yet, when compared with the other states in attendance at the three-day summit in Cornwall, in southwest England, Britain is also by far the most fragile. Simply put: No other G7 member is staring down the barrel of its own dissolution, which Scotland’s potential secession would cause; facing the prospect of a potentially violent dispute over a trade border erected within its own territory, as there is in Northern Ireland; or dealing with the fallout of a diplomatic and economic revolution that was opposed by almost its entire governing class, which is the case with Brexit.

Confronting such a situation, the British government—like its American counterpart—wants to reassert its influence on the world stage, in part to help answer its critics at home. And thanks to the luck of international-summit scheduling, Johnson has an opportunity to do just that, by hosting not only the G7, but also the United Nations Climate Change Conference in Glasgow in November. Taken together, the message Johnson wants to send to his skeptics, domestically and abroad, is straightforward: Britain is back.

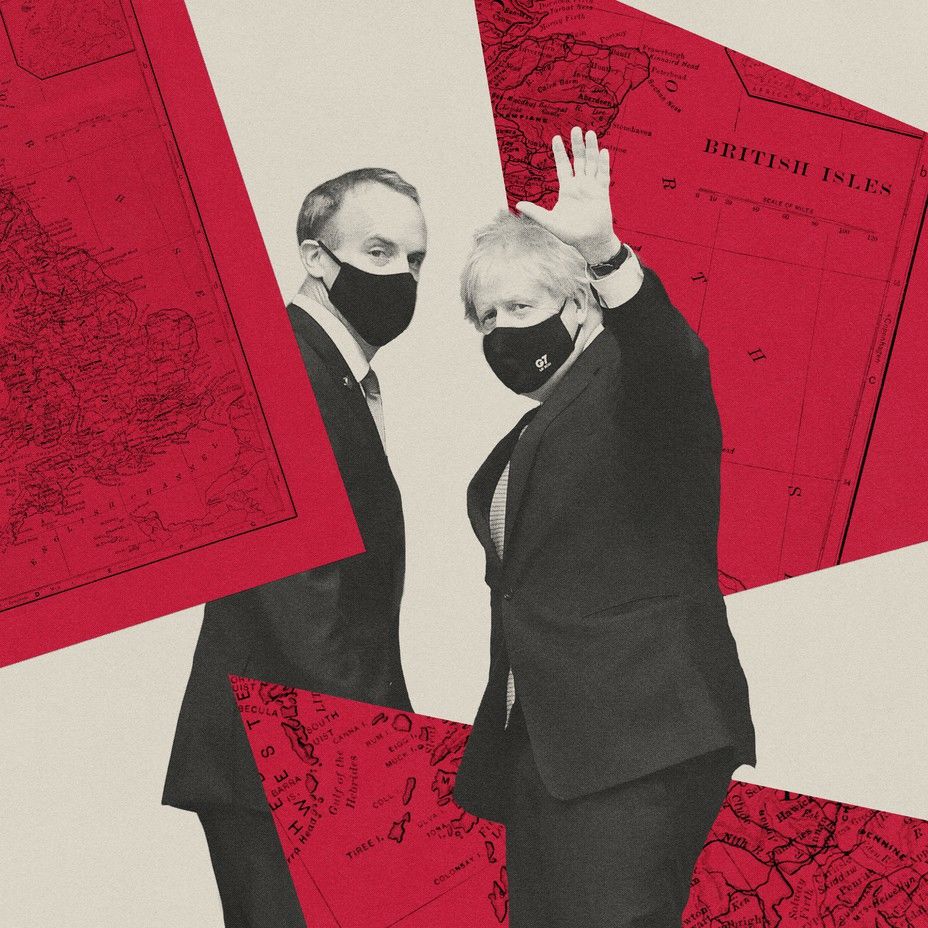

Yet, the very fact that Britain feels it must do so suggests that all is not well. In an interview ahead of the summit, Britain’s foreign secretary, Dominic Raab, told me the G7 was an early opportunity for the country to showcase its new, more “self-confident” foreign policy, dispelling the perception of British withdrawal from the world after Brexit. Twice during our conversation, Raab hit out at the “prejudice” that he feels still exists toward Britain in some quarters, with many lumping Brexit in with what he called “a whole load of other phenomenon,” such as Trumpism and European populism. He dismissed claims that Brexit was a reflection of British nostalgia or “fossilized conservatism,” arguing that such criticism exposed the bias of Britain’s “detractors, not the vision we are articulating.”

This vision, under Johnson, is of a Britain that is faster-moving and more flexible internationally, tilting its focus away from Europe toward Asia and putting its energy into ad hoc alliances and a more robust defense of democratic values to counter threats posed by autocratic regimes such as China and Russia. It places Britain in a more Hobbesian world, in which like-minded countries need to band together when possible, while remaining flexible enough to change course quickly when necessary.

According to those around Johnson, Britain’s foreign policy had become too “ambient” in recent years, revealing a deep-seated complacency about the country’s competitiveness, its global influence, and the security of its democracy. In effect, Britain had been drifting—economically and diplomatically—long before Brexit, the prime minister and his team believe. Its withdrawal from the European Union has acted as a “cold, sharp bucket of water,” according to one influential aide who, like others I talked with, requested anonymity to speak candidly.

The Johnson foreign policy, which was formally set out earlier this year, has strong—and intentional—overlap with the approach of the Biden administration, which focuses on renewing democracy at home and abroad, while building a “foreign policy for the middle class” to meet the aspirations, needs, and values of everyday citizens.

Although much can clearly be said for the Biden and Johnson critiques of previous foreign-policy mistakes, there is also little doubt that this Anglo-American shift comes with its own set of conundrums and questions: Do “values” really trump interests, or is this just a convenient way to preserve Anglo-American power? When does an illiberal democratic ally become an autocratic adversary?

Perhaps most fundamental of all, though, given the events of the past four years in both Britain and America: Is either country fit to act as a leader of any global democratic alliance, even if one could be called into existence?

The G7 is a strange, antiquated institution representing a largely Atlanticist world that no longer exists. In Donald Trump’s typically blunt assessment, the G7 is “a very outdated group of countries” that needs updating to reflect the world of today. When the leaders of Britain, France, Germany, Italy, Canada, Japan, and the United States line up for their traditional summit family photo this weekend, who can really disagree?

The problem was not so much Trump’s analysis of the issue, but his solution. The former president wanted to bring Russia back into the fold, to better reflect global power. He didn’t seem to care much about the “values” bit of the equation. This proposal, made last year, was fiercely opposed by Britain and others, and the only reason an unseemly spat was avoided was because the summit was canceled as a result of the pandemic.

With Trump gone, Britain has decided to use its leadership of the G7 to turn the summit into an informal, if slightly larger, version of an idea that foreign-policy analysts have called the “Democratic 10.” Though the problem it seeks to address is the same one Trump articulated, the solution is entirely different. It aims to replenish the G7 with three democratic (and, not coincidentally, China-skeptic) powers: India, South Korea, and Australia. For this year’s talks, Britain has added another nation, South Africa, bringing the roster to 11.

Britain’s vision complements Biden’s promise to host a “summit of democracies” within the first year of his presidency. Before the election, the American president said that such a meeting would strengthen democratic institutions, but also “honestly confront nations that are backsliding, and forge a common agenda.” Biden’s proposal seeks to address the deficiencies of American foreign policy in recent years, which analysts on both sides of the partisan divide largely accept has failed to adequately challenge autocracies taking advantage of its economic and democratic openness.

Lurking under the surface of Biden’s drive for an alliance of values, then, is an assessment of raw geopolitical power. As well as being a defense of democracy, this wider grouping is also, in effect, a loose concert of powers to contain China and push back against Russia.

Such an alliance—bigger than the G7, but different from the G20, which includes Beijing and Moscow—is attractive to Britain because it offers a stage on which it can sit comfortably and remain one of the most influential members. Meanwhile, America can maintain its role of undisputed leader. The proposal has been greeted with more apprehension by France and Germany, whose leaders dislike the concept of a new U.S.-led alliance that undermines moves toward European “strategic autonomy.” They are also concerned about what they see as the many pitfalls of a policy that seeks to divide countries between democratic and nondemocratic. Where, critics ask, should strategically important countries such as Turkey and Indonesia be placed? What about India, whose own democratic credentials are being questioned?

And if the world’s democracies are meeting in Britain, where are Brazil, Nigeria, and Mexico? Why has the chair of the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) also been invited to this year’s event, when the position is currently held by Brunei, a state that does not even come close to being democratic? The answer that France and others would point out is that, in aiming to build a club for like-minded, largely English-speaking powers, Britain’s foreign policy shows itself to be not values-based, but cynical, seeking to retain its status while building practical inroads into new foreign-policy and trade arenas.

For Britain and America, though, that’s entirely the point. The world must change so that they can stay the same.

Faced with this sort of skepticism, Britain has concluded that it is better to get on with it than try to formally restructure the G7. “The view we took was that: Let’s invite the Indians, the Koreans, the Australians, and the South Africans,” Raab told me. “Let’s just start doing this.”

The foreign secretary said Britain believed that the future would be about testing new developments organically, rather than trying to impose a grand solution from scratch. “I don’t have a particular academic paradigm in my mind for how the D10 would work,” he said. “I certainly don’t feel ready for some kind of organization with structures and applications to join and all the rest of it.” Instead, Britain would pick issues it cared about and try to work with “clusters of like-minded partners.”

Britain is not the first G7 power to try this. In what should have been last year’s G7 summit in the U.S., Trump invited Australia, India, and South Korea, as well as Brazil, while flirting with the idea of re-inviting Russia. The year before, in Biarritz, France invited Australia, India, and South Africa, though not South Korea.

Amid the turmoil of the past few years, then, is more consistency than meets the eye: All Western powers are grasping in the dark for formats to protect themselves in a world in which the West is no longer dominant.

The emerging alliance of democracies remains improvised and informal, without the international heft of alliances such as NATO or semi-sovereign blocs such as the EU. To Raab and others, this lack of structure has its merits. “Our instinct is an internationalist one,” he told me, “but I like the idea of working with partners as a matter of choice, not because we are so fettered.”

In addition to its G7, G20, NATO, and UN memberships, and what London hopes will be partner status with ASEAN, Britain (remember: an island in the North Atlantic) is also seeking to join the Trans-Pacific Partnership, a multicountry trade deal that Trump abandoned after being elected in 2016. Britain hopes to further deepen cooperation with Japan and India as well and, in time, conclude a trade deal with Washington. Johnson believes that this would see Britain as a central node in a vast network of trade and diplomacy. This is his vision of a post-Brexit “Global Britain.”

This international activity, Johnson and his team hope, will act as a political ballast for Britain, helping to strengthen its union by showcasing its continued relevance in the world. Implicit in all of this is the challenge to those in Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland tempted by independence: Britain still matters.

The problem with this strategy has nothing to do with the vision, but with the hole that remains at the heart of it—Europe. “Everything is up in the air because of Brexit,” one Johnson aide told me. “Whatever it is, a glorious or inglorious revolution, there’s a British political revolution with serious and major foreign-policy implications.” With the rest of the world, these implications are starting to take shape: more agility, more alliances, more trade deals. But with Europe, they remain far less clear.

Ultimately, in the Johnsonian worldview, Brexit will act as a spur for Britain to work harder to maintain its influence and prosperity, forcing it to be more flexible and creative in its approach. Trying to be a “status-quo power” is no longer enough. But Britain cannot formulate a long-term strategy for its relationship with its most important allies across the Channel because it does not yet know what kind of relationship it is going to have with the EU. Today, nearly five years after the Brexit vote itself, questions persist over the depth of the economic partnership that will develop, and whether relations will settle into easy amiability or tense competition.

The irony, then, is that Britain’s shift toward a more agile foreign policy might be strategically sound, but its desire for more international influence would be helped if it were more settled domestically, and in its near neighborhood.

The conundrum therefore remains: Success on the world stage can help ward off fragility at home. But that very fragility makes it harder to succeed globally.