Margaret & Diana & Elizabeth & Nancy

The scene comes early in the first episode of The Crown’s fourth season: a drawing-room confab between two of the most powerful people in the world, a veteran ruler and an upstart newcomer. The year is 1979. The Queen (played once again by Olivia Colman) nervously adjusts a vase of flowers—the gesture of a woman subliminally preparing for the scrutiny of another woman’s gaze. When Margaret Thatcher (played by Gillian Anderson) enters the room, she proffers a curtsy so low that her royal-blue skirt scrapes the floor. “Your Majesty,” Anderson sighs, her gravelly baritone an approximation of the voice that the theater director Jonathan Miller described as “a perfumed fart,” and that the journalist Clive James likened to “a cat sliding down a blackboard.”

One moment, Thatcher is discussing her proposed cabinet of government ministers with the Queen and explaining that she finds women “too emotional” for high office. The next, she’s at home with her husband, Denis (Stephen Boxer), recounting the events of the day while pressing pillowcases. (Insert your own “Iron Lady” joke here.) The head of the British government, for the first time, is also a housewife—a woman who dishes up kedgeree to her speechwriters at 4 a.m. and sternly tells a maid who tries to unpack Denis’s weekend bag that such an intimate act is “a wife’s job.” In The Crown, as in real life, Thatcher wears her femininity and matriarchal identity like a flag: stiffly, patriotically, and to signal to her enemies that trouble is on the horizon.

For tabloid junkies and esteemed Windsorologists alike, the fourth season of The Crown is a major event. After spending 30 episodes sifting through events as somber as the Suez crisis and the Aberfan mine disaster, finally we get to the really juicy stuff: the troubled relationship between Thatcher and the Queen, the political turmoil in 1980s England, and, most crucial, the turbulent marriage of Prince Charles and Lady Diana Spencer. Diana, played with wan fragility by the newcomer Emma Corrin, threatens to overshadow the season, just as she upstaged the more homely royals during her lifetime. But Peter Morgan, who created The Crown and wrote or co-wrote all 10 new episodes, seems equally fascinated with Thatcher, and the way her relentless individualism collided with the Queen’s well-worn sense of collective duty.

To watch The Crown alongside The Reagans, Showtime’s new documentary series about America’s own lustrous ’80s-era dynasty, is to see four different models of female power colliding with history, and with one another. The Queen embodied privilege and notions of hierarchical responsibility that, in a decade defined by capitalist excess, were quickly becoming old hat. Thatcher was pure political power: an antifeminist committed to spreading the gospel of self-interest. Nancy Reagan, crowned the Iron Butterfly by her detractors, was the epitome of soft influence, whispering in her smiling husband’s ear. And Diana, from whom nothing was expected but quiescence and children, became a model for seizing power as a populist. Marrying into a family that had long taken stoicism to the extreme, the “people’s princess” demonstrated how potent public vulnerability could be.

A decade after her death in a car accident in 1997, Diana continued to divide Britons into two camps: those who saw her emotional transparency as vulgar and manipulative, and those who admired her for challenging the Victorian frigidity with which the House of Windsor had previously treated its own heirs. “The genuinely bizarre aspect of the all-consuming Dianamania that gripped Britain a decade ago this week is how slight a trace it has left behind,” my colleague Anne Applebaum wrote in Slate in 2007, dissecting the idea propagated by columnists after Diana’s death that she’d changed the monarchy—and the country—forever. But of the four 1980s women returning to the spotlight this month, Diana seemed to best predict what wielding power in the 21st century would look like, when ginning up perpetual chaos is easily accepted by an aggrieved populace that suddenly feels not only seen and heard, but cared for.

The Crown’s Thatcher doesn’t look like a radical: Played by Anderson, Morgan’s partner, she’s a late-’70s aesthetic horror show of hairspray, pussy-bow blouses, cobalt tailoring, and chin thrusts. The new prime minister is a steamroller in search of an uneven surface; less a traditional conservative than an extremist in Tory clothing, her desire, she explains, is to impose on her unwitting electorate “one of the boldest and most far-reaching programs of fiscal correction this country has ever known.” As education secretary, she’d been nicknamed Maggie Thatcher the Milk Snatcher for cutting a program that gave free milk to middle-school students. Now leader of the country, she seems similarly inclined to wean it off welfare.

Yet she isn’t exclusively unsympathetic, at least in her dramatized form. Morgan takes time to depict her as an underdog: She spends a long weekend with the Queen at Balmoral Castle in Scotland, where a series of invisible tests sorts the upper-class wheat from the upwardly mobile chaff. Thatcher, a self-made workaholic, neglects to bring “outdoor shoes.” “What are you doing?” Princess Margaret (Helena Bonham Carter) asks Thatcher, appalled, when she finds her working in a corner of the drawing room instead of accompanying the Queen outside. Thatcher begs Her Royal Highness’s pardon. “Begging for anything is desperate,” Margaret replies, witheringly. “Begging for pardon is common.”

The Crown nods fleetingly to Thatcher’s antifeminism—how she disdained women and girded herself against weakness even while insisting on maintaining her wifely standards. (No other prime minister, one imagines, has worn an apron while entertaining the heads of the armed forces.) But Morgan’s portrait of Thatcher lacks the sexual dynamic that imbued many of her relationships with powerful men—one she used to full advantage. François Mitterrand once described her as having “the eyes of Caligula and the lips of Marilyn Monroe.” Philip Larkin called her a “superb creature … right and beautiful.” Anthony Burgess, writing for Vanity Fair, recalled being struck by the “powerful femininity” and “sexual aura” she exuded as a leader. “The masochist in all men,” he wrote, “responds to the aggressive woman, and recognizes that her charm lies in the appearance of velvet and the reality of iron. Political power will never be sustained by the woman who is a frump.” For a generation of Englishmen who were ignored by their mothers and raised by exceedingly stern nannies, Thatcher’s scolding manner must have seemed reassuringly familiar. The satirical puppet show Spitting Image often portrayed her smacking members of her cabinet like schoolboys.

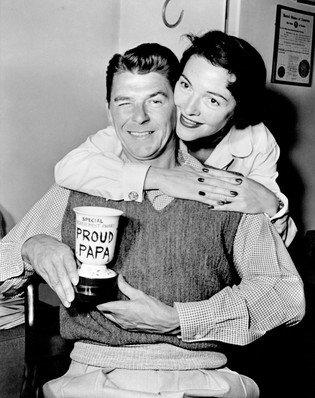

In the U.S., Nancy Reagan conjured a similar nostalgia, but one channeled in a different direction. The myth of Ronald and Nancy, Joan Didion once argued, was that the ’60s had never happened. Men were swaggering and square-jawed and generously compensated for doing not much at all. Wives were doting and manicured and delicately clad in floral silk. In a scathing profile for The Saturday Evening Post titled “Pretty Nancy,” Didion described the then–California governor’s wife as having “the smile of a woman who seems to be playing out some middle-class American woman’s daydream, circa 1948.”

The Reagans argues that Nancy was the real power in the marriage, and the guiding force behind the couple’s mythmaking. “She was like the studio head,” the journalist Lesley Stahl tells the camera. “She was the consigliere.” If Ronald Reagan was the sunny public face of the pair’s power, Nancy was the force propelling them upward. The couple met, the series explains, when Nancy, a working actor, finagled a meeting with Ronald, a divorcé who was then president of the Screen Actors Guild, and quickly began taking care of him. Nancy could be pragmatic: Although she wanted to quit acting, she took a job on a low-budget B movie, Donovan’s Brain, after their marriage in 1953, because the couple needed money.

Across the Atlantic, Thatcher was forging a path dedicated to downsizing government. But the force motivating the Reagans was much simpler. Nancy, who grew up poor before her thespian mother remarried a doctor, was anxious about money and fond of luxury. Both she and Reagan were actors accustomed to being tended to, who saw nothing particularly strange about others picking up the bills, whether it was General Electric outfitting their dream house in a “living advertisement for corporate America,” as one talking head puts it, or Reagan’s “Kitchen Cabinet” of donors paying to refurbish the White House to Nancy’s exacting standards. And if the Reagans managed to get rich, the theory went, nobody else had an excuse not to. “You can increase your own prosperity for the good of others” was Thatcher’s pretzel logic. As The Reagans interprets it, Nancy’s economic insecurity was a means through which wealthy donors could become benefactors, leaning on the president to cut taxes in the process.

In public, Nancy was an adoring and passive wife, known for the gaze she’d fix intently on her husband. “I agree with everything he said; I always do,” she once told an interviewer. But behind the scenes, aides came to see the breadth of her power. She religiously consulted an astrologer for matters as trivial as scheduling and as significant as the compatibility of Ronnie and Mikhail Gorbachev. Her “Just Say No” antidrug campaign, the series suggests, was the epitome of Reaganite self-sufficiency extended into public policy, blind to shades of circumstance and obstinately stuck on the idea of individual choice. Late in the Reagan presidency, most people assumed that Nancy was influencing her increasingly fuzzy husband, who was later diagnosed with Alzheimer’s disease.

History expects women to be moderating influences on men. It requires of women a capacity for care that it doesn’t demand from male leaders. And it rarely favors women like Thatcher and Nancy Reagan, who appear to be interested above all in their own ability to thrive. The Crown never suggests that the forces motivating Princess Diana were entirely selfless and altruistic, but it conveys how attuned she could be to the public mood, and how deftly she was able to respond. In the fourth season, Diana Spencer arrives at Balmoral for what amounts to an audition before the Queen. Every test that Thatcher failed, Diana aces. As Prince Charles (Josh O’Connor) recounts to his girlfriend, Camilla (Emerald Fennell), the performance garners her “rave reviews from the whole ghastly politburo.” Diana is demure. She’s discreet. Her weekend luggage contains nothing but outdoor shoes. Her entire life, she’s been raised and trained for exactly this moment, a prize calf in a pie-frill collar and pearls.

Yet, as the third episode of The Crown’s new season, “Fairytale,” depicts in horror-story style, Diana’s induction into the royal family slowly breaks her down. In the weeks leading up to her marriage to Prince Charles, when her newfound celebrity makes living in her Earls Court flat untenable, Diana is moved quietly into Buckingham Palace, and then abandoned. Her fiancé departs for several weeks and refuses to take her calls. The Queen ignores her entreaties for a meeting. Hundreds of letters and bouquets are brought to her room each day, a ghastly foreshadowing of the public outpouring of grief after her death, when many London florists ran out of stock. Left alone, Diana binges in the palace kitchens and purges in her room. She roller-skates through staterooms. At Charles’s suggestion, she has lunch with Camilla Parker-Bowles, during which it becomes clear that not only is her husband still in love with another woman but Diana barely knows him at all.

In the show, the Firm—as insiders call the royals—puts Diana through a hazing process intended to keep her pliable, dutiful, and in her place. But in depriving a woman barely out of her teens of company, activity, and affection, the Crown miscalculates. Diana becomes depressed, and develops an eating disorder. She also becomes more receptive to the adulation of strangers. Morgan depicts a just-engaged Diana walking to work at a preschool one morning surrounded by photographers, a ghost of a smile on her face. Later, while she’s on a royal tour of Australia with her husband and baby son, crowds start gathering for a glimpse of a woman who unabashedly presents herself as a mother first and a princess second. In public, she chats and notices people’s outfits and takes photos and smiles and smiles and smiles. “She’s amazing,” onlookers gush. “She’s just like us.”

If Diana’s accessibility cemented her stardom, it also doomed her marriage. Noting that crowds sometimes audibly complained when Prince Charles walked down their side of the street, his wife on the other, the journalist Alex Witchel observed in 1992 that “princes don’t like to be groaned at, especially Charles, who’s spent his entire life being obscured by his mother, only to be upstaged by his wife.” The more Diana connected with ordinary people and touted her bona fides as a hands-on mother, the more she showed up the royals for their stiff upper lip and starched repression. Nor was Diana’s influence purely self-serving. The Crown recreates the moment in 1989 when the princess spontaneously hugged a child with AIDS in a Harlem hospital, dominating headlines and humanizing a crisis.

Although Nancy Reagan and Diana both understood the power of optics, Diana was able to harness empathy to devastating effect. Where the Queen presented herself as a serenely detached and almost divine mother to a nation, Diana intuited that what people wanted from their benign—if fundamentally undemocratic—sovereign was connection. Thatcher wielded power with such an oppressive hand that few complained when her own party deposed her. But the age of royals on Instagram, of celebrity presidents, of crying openly on camera, was something only Diana’s peculiar fame anticipated.