'Sextortion' attacks on the rich and famous are on the rise. Here's how their lawyers discreetly fight back.

A young Manhattan CEO looked at his phone in horror. "I'm going to blow up you and your business," the screen read.

It was a woman he'd met on Seeking Arrangements, the so-called sugar-daddy site. She'd told him she was of legal age. Now she was claiming otherwise.

The CEO had already parted with some $40,000 in money and gifts, first willingly, and then, after their breakup, in response to her threats.

Now she wanted more money, or she'd publish their intimate sexts on his social media accounts and accuse him of statutory rape. And he didn't even know her real name.

"If you can't get me money," she texted the terrified CEO, according to records reviewed by Insider, "I'm going to fuck up your whole company."

"It's always the same thing: 'Pay me, or I'm going to blow up you, or your marriage, or your business,'" says Jeremy Saland, who specializes in the growing, lucrative, highly-secretive legal field of high-end sextortion defense.

"It's always, always a crime," says Saland, a former Manhattan prosecutor.

Yet the last thing these clients want to do is tell the police. They're panic-stricken at the thought of their name popping up in a lawsuit caption or a gossip-website headline.

Be they NBA stars, or Hollywood A-listers, or no-name Manhattan millionaires, all they want, and want desperately, is for the sextortion to quietly stop. They pay tens of thousands of dollars to the lawyers who make that happen.

"To them, coming to us is like they're handing us a ticking time bomb that they want no one to know about," said Herman Weisberg, a private investigator who's worked these cases with Saland for a dozen years.

"They think the world is about to end."

East Coast, West Coast

High-end sextortions like the case of that Manhattan CEO, one of Saland and Weisberg's recent clients, are spawning a growing legal practice. Business right now is booming, lawyers who specialize in these cases agree.

These are not legitimate, "#MeToo" cases, but rather blackmails based on false accusations. The clients are men almost exclusively, largely based in Los Angeles and New York, with each coast seeing a different pattern of target and attack.

LA lawyers say they see more A-listers — entertainment and sports stars — who are threatened with multi-million-dollar bogus lawsuits.

"These are cases where I send my investigator out, and the accusation is not real — it's a shakedown," typically for seven figures, says LA lawyer Shawn Holley, who sees it as a big win when she can negotiate an out-of-court settlement in the low five-figures.

Sometimes the celebrity will want to publicly fight the false accusations, says Holley, a partner at Kinsella Weitzman Iser Kump Holley LLP. But managers and agents quickly talk them out of it. The reputational damage, even if the celebrity is eventually proven innocent, is too costly.

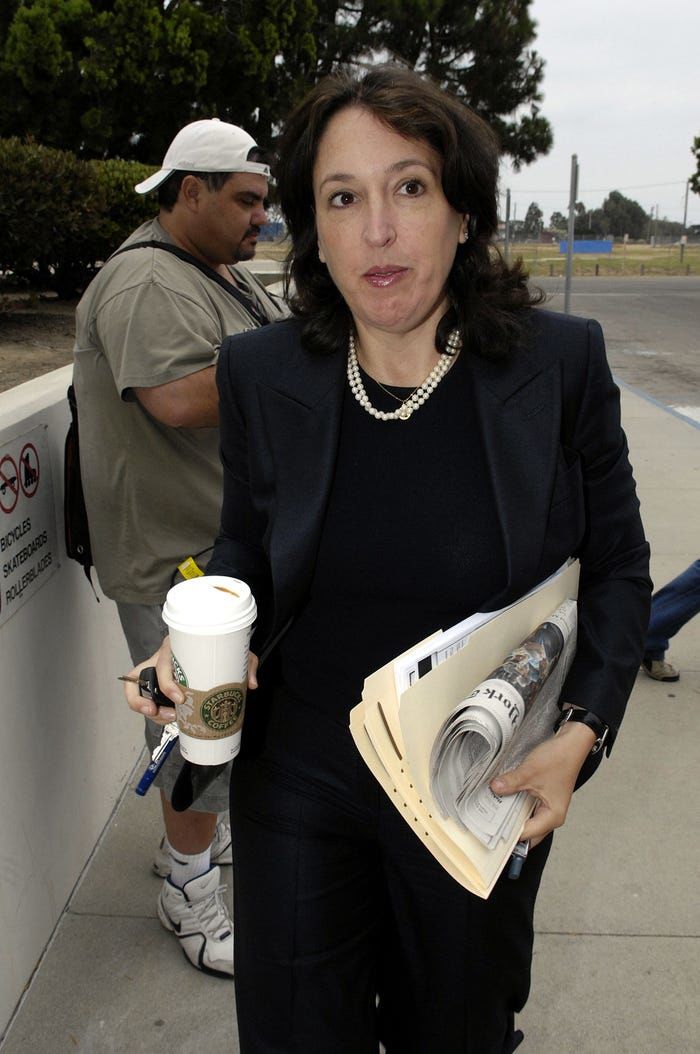

Shawn Holley representing Lindsay Lohan in Los Angeles in 2013.

Shawn Holley representing Lindsay Lohan in Los Angeles in 2013.

"I tell them, 'It's the cost of being you,'" Holley — a member of O.J. Simpson's "Dream Team," whose clients have included Kim Kardashian, Snoop Dogg and Lindsay Lohan — says of the 15 or more celebrity sextortion cases she quietly makes go away each year.

"There's been a significant increase over the last 20 years, but in the last five or six years it seems to have exploded," says Blair Berk of Tarlow & Berk, PC, another celebrity lawyer out of LA.

"Typically it's clear there's been no wrongdoing," says Berk. "It's a clear red flag when part of the extortion is the threat to go to law enforcement, but they say they've chosen not to."

"The victim is told, 'I'm going to file this in court next week unless you come to the bargaining table," says John B. Harris, of Frankfurt Kurnit Klein & Selz, of the typical LA celebrity shakedown.

"It gives the well-known person obvious fear" of bad publicity, Harris said, which is why out-of-court settlements often come with non-disclosure restrictions and payment schedules that stretch out over time, to incentivize the sextortionists' continued silence.

It's different in Manhattan

In contrast, Manhattan sextortion clients tend to hail not from the A-list, but from the city's vast pool of the anonymously wealthy. And the sextorters confront their marks directly, without a lawyer at their side waving a draft lawsuit.

"I see hedge fund managers, private equity partners, big law firm attorneys, high-end physicians, especially those with active social media platforms," says Saland, who estimates he and Weisberg have worked some 200 cases in the last dozen years.

Their clients are often Manhattan-based, though the sextorters, both male and female, come from all over.

"We've handled cases where we've had to track people down in the Philippines," says Saland, "and we found someone in Kenya who was extorting a young kid on Instagram" after tricking the kid into sending nude photos, he adds.

The threats can follow an extramarital fling, a bender in Vegas, or a "date" with a sex worker from websites like Ashley Madison or Eros. Sometimes it's after a dalliance, even just online, with someone who is transgender or of the same sex.

"They're vulnerable, whether it's their closeted sexual preferences, or because of their familial relationships," Weisberg says of the wealthy targets.

"Sextortion is an ugly term with ugly repercussions," says Stacey Richman, a Bronx-based criminal defense attorney with a national, high-profile clientele.

"For some, it's a business," she says, especially in the darker corners of the online sex trade.

"For some, it's a lottery. And the risk of exposure is absolutely terrifying, because in our country, you cannot get your reputation back, really," she adds.

"You are forever sullied. And it's tragic because it debases true victims."

NFL, NBA players a favorite target

Lawyers on both coasts say they have seen a hike in shakedowns of young athletes, particularly in the NBA and NFL.

"You have kids that have grown up in wholesome families. They've devoted their lives to their sports. They're not partiers," Richman says.

"And then they meet some of these people —" Richman divides them into two groups, "predators" and "obsessives" — "and it can be devastating."

"They hit the young athletes," says Weisberg. "And they're 21 years old, and they're in a strange city, maybe in New York for the first time. These guys actually are lonely.

"And somebody on Instagram says, 'Hey, what are you doing after the game tonight?'

"Then all of a sudden we've got a young guy calling us saying he's got a wife and babies or a girlfriend who's pregnant who can't find out about whatever happened, either online or in person. And that the team's going to get pissed at him."

Anatomy of a sextortion defense

Every sextortion defense case starts in the same way, Saland, an ex-prosecutor, and Weisberg, a former NYPD detective, told Insider in a recent interview.

They talk the client down from a ledge.

The CEO whose Seeking Arrangements "date" was now threatening to "blow up" his business? Take a deep breath, Saland says he told the panicking man, as he tells all new clients.

"They're not going to blow you up," Saland says he assures them. "Because you're the golden goose."

"They only have one hand grenade to throw," explains Weisberg of the would-be blackmailer.

"And if they throw that," agrees Saland, "that's it. They've lost their money."

In the case of the CEO, the woman never gave her real name or address. Saland and Weisberg needed to determine who she was, and that she was indeed of legal age, before agreeing to take the case.

The two say they turn down clients who are being extorted over actual criminal behavior such as drug abuse, domestic violence, or sex crimes.

"There's no judgement," says Weisberg, "as long as our guy is the victim."

But in his panic, the CEO, like most clients, had blocked the woman's number and was on the brink of deleting her texts — an evidentiary no-no, Saland and Weisberg say.

"If there's text messages, give them to me," Saland says. "If there's phone calls, get me the logs. Do not delete. Do not block. That way they're giving us more evidence by sending more threats."

"Don't edit," adds Weisberg. "We tell people all the time. You're basically in the doctor's office. If you don't tell us everything, we can't help you. If you don't take your pants off in the doctor's office you're not getting a good exam," he says with a laugh.

Pictured are attorney and

former prosecutor Jeremy Saland, standing, and private investigator

Herman Weisberg, a former NYPD detective. Based in Manhattan, the two

collaborate in fighting "sextortions" targeting wealthy clients.

Pictured are attorney and

former prosecutor Jeremy Saland, standing, and private investigator

Herman Weisberg, a former NYPD detective. Based in Manhattan, the two

collaborate in fighting "sextortions" targeting wealthy clients.

Both Saland and Weisberg fought and won their first big extortion cases while working for the Manhattan DA's office.

In 2005, Saland won a three-year prison term for a man who tried to shake down NBA star Carmelo Anthony for $3 million. In 2010, as a DA investigator, Weisberg helped crack the David Letterman blackmail case, in which a television producer threatened to reveal Letterman's extramarital affairs with female staffers.

Now, they put that law enforcement experience to work for sextortion victims who pay top dollar, generally between $30,000 and $75,000 per case.

"Is there a Zelle payment? Is there a PayPal payment? Were there phone messages? Now we have a name. I'm looking for the same evidence I would seek as a prosecutor," says Saland.

"It's basically a skip trace," says Weisberg.

Each case is different, but generally, the two begin to build a dossier on the sextorter. They gather enough information to turn the tables, sometimes, if the client agrees, by quietly filing a family court petition if a domestic relationship is involved, and often by drafting a lengthy, carefully researched and worded "cease and desist" letter.

Both the family court petition and a cease and desist letter will warn the sextorter that an investigation has revealed their accusations to be false, and that their behavior is criminal.

"Having an affair isn't illegal," says Weisberg.

"But, you know what, telling someone 'I'm in front of your house at four in the morning and I'm going to ring your doorbell and tell your wife we're having an affair if you don't pay me,' that's illegal. That's attempted grand larceny."

A surprise visit

In the case of the CEO, Weisberg's investigation, which included records searches and surveillance, eventually determined that the young woman was suffering from drug addiction and living outside Manhattan with a man she called her "manager."

"At first I couldn't get to her," Weisberg remembers of the woman, who would communicate only through a hard-to-trace "VoIP," or Voice over Internet Protocol connection.

But Weisberg's staff found her, and were hidden outside her apartment one day when she and her manager came outside for a smoke break.

"So I called her, and I had this video feed on her at the time," Weisberg recalls.

"And she put the guy she called her 'manager' on the phone. And he was extremely aggressive and chesty with me, saying 'Fuck you! He's going down!' meaning the CEO."

"And I was able to tell her, your boyfriend? He should be careful what he carries in that knapsack, because I know there's a lot of weed in there, because he just took it out."

Weisberg went on to describe what both of them were wearing —"I said, 'you're wearing a big track suit, with a rainbow thing going up the side, and your boyfriend's got a multi-colored hat with a backpack I saw him take weed out of."

Then Weisberg pointed out the police car that happened to be parked, by coincidence, down the block.

"I just love that moment when she thought I was never going to find her, and there I was, looking at her," Weisberg remembers.

"She started looking around. And I said, "Yeah, look more to your right. You see that radio car right there?' I wish I could play you the tape, because the changes in their voices were remarkable."

Saland's seven-page, single-spaced cease and desist letter — which omitted any identifying details about the client, so it couldn't be "weaponized" against him — rattled the woman and her manager still further.

"As you read the following, I encourage you to seek counsel, or speak to your father, Mr. [name redacted], to best understand the consequences of your actions," it began.

Soon enough, "He ran away with his tail between his legs, and she went back home to her family," out of state, says Weisberg.

"I never threaten. Herman would never threaten," Saland says.

"I just lay out the criminal conduct, and the law that you have violated, and explain that our client is going to exercise his or her rights to the fullest extent of the law, just like with any other crime."

You won't find reviews online, Saland says with a laugh. "They never write, 'Thank you for all the help with that extortion.'

"But people are incredibly grateful."