The U.S. is reducing its reliance on China for green technology. Could that slow progress on climate change?

The annual United Nations climate conference is underway in Egypt, and the world’s two largest emitters — the U.S. and China — are hardly talking. After House Speaker Nancy Pelosi (D-Calif.) visited Taiwan last summer, infuriated Chinese leaders retaliated by cutting off dialogue with the U.S. on key issues including climate change. At last year’s climate conference, the U.S. and China came together despite deteriorating relations to announce a list of joint climate priorities; but any effort to coordinate seems off the table for now.

It’s bad enough that the U.S. and China aren’t cooperating on a critical issue many experts had hoped might offer some common ground in an increasingly fraught relationship. And now another geopolitics-meets-climate issue is rearing up outside the negotiating halls.

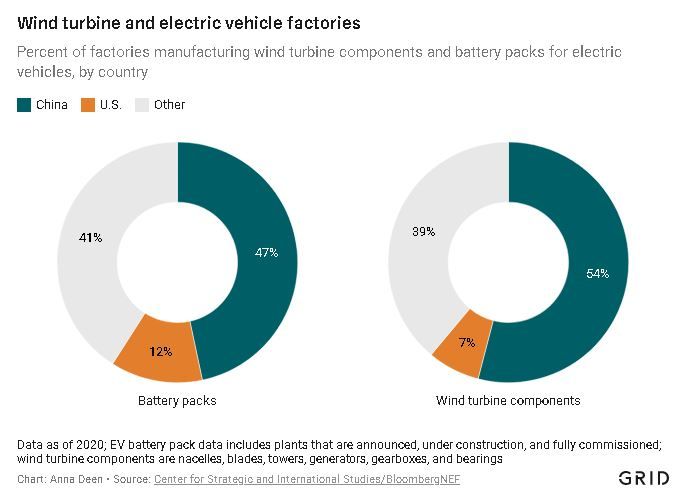

For the U.S. and other Western countries, a national security concern — the potential overreliance on China for technology — has been paired with the economic fear of missing out on the windfall of the green energy transition. Taken together, these concerns have prompted a rethink of global supply chains. The U.S. has introduced a slew of policies — including the Biden administration’s landmark climate law, the Inflation Reduction Act — to reduce dependence on China for green technology, and to build more solar, wind and battery factories at home.

“I think this reliance on Chinese key industries has become really uncomfortable for folks in the U.S.,” said Jonas Nahm, an assistant professor of energy and environment at Johns Hopkins University. That discomfort, Nahm said, has resulted in a push “to diversify away from China and localize as much of this production as possible.”

As the U.S. pursues its looming climate goals — such as ensuring that half the cars sold in the U.S. are electric by 2030 and reaching 100 percent zero-carbon electricity by 2035 — it stands to reason that policymakers would want a lot of that green technology to be made in America.

But at this critical moment when the U.S. must move faster to reduce emissions, building up new supply chains at home could cause critical delays. Globalized green technology supply chains — many of which originate in China — have played a big role in helping countries wean themselves off fossil fuels by driving down costs. And a break in that trade going forward risks further damage to the planet.

“Many countries have introduced or started to introduce trade barriers to block the free flow of goods, capital or talent, so potentially we have raised the cost for renewables,” said Gang He, an assistant professor who focuses on energy policy at Stony Brook University. “That presents a dilemma. That to protect the climate, we need cheap renewables, but countries are doing the reverse thing.”

The climate price tag of shutting U.S. borders to trade

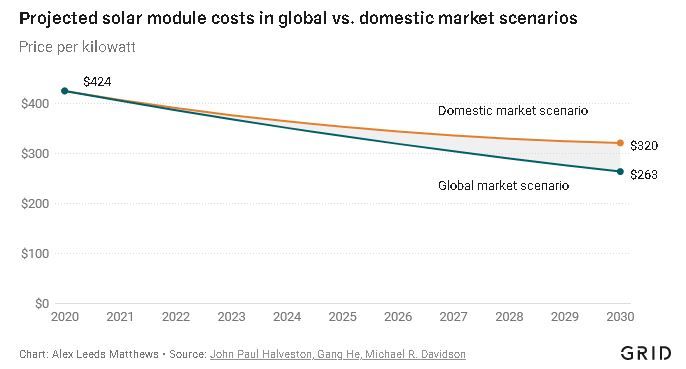

As countries face this “dilemma,” a new study published in Nature provides a warning. The study looked at a hypothetical scenario that has become much more plausible: Had the U.S. and Germany decided to produce all their own solar panels domestically over the last decade, the price of those panels would have skyrocketed — 107 percent higher for the U.S., and 83 percent for Germany. The problem cut both ways; for China, shutting itself off to the outside world would have meant a spike in solar panel prices of around 50 percent. Together, all three countries saved some $67 billion by keeping the channels to global markets relatively open, allowing solar companies to learn from each other and drive down costs.

These three countries are among the world’s top installers of solar panels, and as they aim to rapidly solar power installation in the coming years, the same dynamic will hold true. The researchers found that if all three had decided to start shutting their borders in 2020 and shift to domestic production, by 2030 costs would be 25 percent higher.

For American pocketbooks, there’s a clear takeaway. “Think about if you want to install a solar system on your roof, you’ve benefited immensely from this reduction in costs associated with global supply chains,” said Michael Davidson, an assistant professor of engineering and energy policy at the University of California, San Diego, who co-authored the paper. “It’s unclear how we can continue to lower the costs of those types of systems that many U.S. consumers are benefiting from if we try to go it alone.”

Beyond the consequences for American consumers, there are also important stakes for the global thermostat. “If you’re concerned about reducing emissions as fast as possible in order to address our climate goals, we need to have very low-cost clean energy and it needs to be getting even cheaper in order to do so,” said Davidson. “But there are many policies now that could fundamentally change that learning curve. Those would be very problematic for meeting our long-term goals.”

Is the U.S. trying to go it alone on green technology?

In the Nature study’s scenario, the U.S. decides to fully shut down solar imports and manufacture all the solar panels it needs domestically. The U.S. has no such policy — yet — but cumulatively, several measures are moving the U.S. away from global supply chains and toward a made-in-America future.

The trend isn’t exactly new. Starting a decade ago, the U.S. imposed tariffs on Chinese solar panel imports, based on findings that the panels were produced using unfair subsidies and dumped on the U.S. market at prices that undercut U.S. companies. The Trump administration added additional solar tariffs that President Joe Biden weakened but didn’t fully remove. The policy has been somewhat effective: It has helped First Solar, the only American company in the top tier globally, remain competitive and brought additional manufacturing to the U.S. But the tariffs alone have failed to bring about a great U.S. solar revival.

Biden took office with a fresh focus on tackling climate change, and his administration has expanded beyond tariffs to increase domestic green technology production. The cornerstone of that effort to date is the Inflation Reduction Act, passed by the narrowest of margins this summer. The law provides financial incentives for companies to produce solar, wind, batteries and other green technologies in the U.S.

Among the law’s goals, the targets for domestic battery production may be the hardest to reach, climate policy experts told Grid. The law provides a generous $7,500 tax credit to consumers looking to buy an electric vehicle — but conditions apply. Namely, beginning in 2025, none of the battery minerals can come from China or Russia. That will be a very difficult requirement to meet; China dominates the refining of battery minerals. For instance, almost all of the world’s graphite — one of the main ingredients in these batteries — is refined in China. The law means that all that graphite will be off-limits for an American EV maker, if the company wants its cars to be eligible for tax credits.

The law goes farther. Beginning in 2023, in order for a car to be eligible for the tax credits, 40 percent of the minerals must be mined in North America or countries that have a free trade agreement with the U.S. The U.S. mines and refines very few of these minerals domestically, as Grid has previously reported. In addition, at least half of the battery components must be manufactured in North America. And again, none of those components can be sourced from China. Those requirements get ratcheted up by 10 percent every year.

Nahm said that compared to mining and refining, U.S. companies may be able to ramp up battery manufacturing relatively quickly. Already GM, Ford and other U.S. auto giants have announced plans for new plants to make batteries and their components in the U.S.

But for American car companies, meeting all of these requirements will take some time — meaning consumers may not be able to enjoy those tax credits in the short run. “If everyone now sits at home, and it’s like, ‘OK, so maybe in three years I get 7,500 bucks, but I’m not going to buy a car now.’ … I mean, we are losing three years during which people are maybe buying gasoline cars to replace their existing cars,” Nahm said. “So it does sort of delay everything at a time when we don’t have much time.” In other words, if few car models meet the criteria for the tax credits, the credits may not be very useful as a climate policy — at least not in the short term.

Joanna Lewis, an associate professor of energy and environment at Georgetown University, agreed that the emphasis on domestic production for green technologies could make it difficult to meet the nation’s climate targets. “I don’t think they will be easy to meet by any means,” she told Grid. “And I think companies are already sending those signals.” Another risk is retaliation. This week, the EU issued a formal complaint to the U.S., saying the subsidies violated World Trade Organization rules, and China may follow suit.

The Biden administration has rolled out other policies that are all about strengthening U.S. green technology production. In June, Biden authorized the Energy Department to use the Defense Production Act to boost domestic production of solar energy, heat pumps and other green-tech staples — essentially making the case that these goods are critical to U.S. national security. The act allows the White House to direct companies to produce certain goods, as was the case during the pandemic.

Also in the mix is the Uyghur Forced Labor Prevention Act, passed earlier this year. The law has nothing to do with climate change on its face; it bans the import of goods and raw materials made in Xinjiang, under the presumption that they were made using forced labor. But much of the world’s polysilicon, a key raw material used in solar panels, is made in Xinjiang, and the policy has led border agents to impound more than 1,000 solar shipments at U.S. ports in the last five months, Reuters reported. That has led to significant delays in solar installations in the U.S.

Taken together, these human rights, trade and climate policies amount to a strong movement to reduce ties to China and boost domestic production of green technology. But from a climate perspective, those policies are undeniably complicating the task of decarbonizing the U.S. economy.

A balancing act

For all the challenges, there are clear benefits to bringing certain supply chains back to the U.S.

In the long run, building up domestic clean energy industries could help build the case for climate action. The theory goes: As clean energy companies grow stronger, so too will their lobbying power, helping to pass future climate legislation. This may even extend to red and purple states; many of the battery and solar factories that have been announced are going up in states, including Georgia and Ohio, that have to date been slow to embrace climate-friendly policies.

And there is a clear economic rationale as well. For U.S. clean tech supply chains that are the most heavily reliant on China — such as solar panels and batteries, American companies face a real risk of a supply shock in the event of a natural disaster or conflict. On the national security front, the risk of relying on China for most of these supply chains is fairly low, a recent Science study concluded, but batteries are needed for military applications like drones, so bolstering domestic supply lines is worth additional investments.

Ultimately, the U.S. faces a difficult balancing act, and the climate crisis is unforgiving. “I think competition with China can be very positive for motivating us to do something,” said Nahm. But, he added, “we have to walk a tightrope here with a system that’s not very good at walking tightropes, because there’s a lot of potential for … shooting ourselves in the foot in the process.”