Germany’s nuclear opposition wavers as energy crunch fears rise

Germany’s nuclear cliff edge is crumbling.

The country’s three remaining nuclear power plants are scheduled to shut down at the end of this year — the grand finale of a decade-long plan to end the use of atomic power enacted under former Chancellor Angela Merkel in the wake of the Fukushima disaster.

But driven by fears of Russia's energy blackmail, Berlin is assessing the risks of a winter power crunch and opposition to delaying the phaseout is softening — including among the Greens.

In recent days, senior Green politicians have signaled they are prepared to keep nuclear power plants running for a few months longer, stretching the remaining fuel supply into spring to keep the lights on.

“If we have a real emergency situation, that hospitals can’t work anymore … we have to talk about [stretching] the fuel,” said Katrin Göring-Eckardt, a Green vice president of the Bundestag, on a talk show this week.

The issue is splitting the party.

Several Green heavyweights and regional branches have voiced opposition to any extension, while others, notably in southern Germany, say security of supply is now the paramount issue.

A similar debate is raging in the Social Democratic Party — part of the ruling coalition alongside the Greens and the liberal Free Democrats — whose members also aren’t keen on nuclear power.

But delaying the phaseout would be a particularly bitter pill to swallow for the Greens — a party that emerged from Germany’s anti-nuclear movement — and would face fierce opposition from many of its members.

The Bavarian problem

A key argument for Greens and others opposing a delay has been that Germany faces a gas crisis, not a power crisis. But there’s growing concern that this could change.

As nuclear plants can’t replace gas needed for household boilers or industrial processes, Berlin’s focus has been on substituting gas volumes after Russia started throttling supply.

Gas also contributes around 15 percent to Germany’s power mix, and the government has decided to reactivate coal plants to deal with a potential electricity shortage. But that might not be enough.

The government has decided to reactivate coal plants to deal with a potential electricity shortage

The government has decided to reactivate coal plants to deal with a potential electricity shortage

Coal supply issues, a rush on electric heaters and the precarious situation of southern states have raised fears that a gas shortfall could also push Germany into a power crunch.

The economy ministry was concerned enough that it launched a “stress test” of the grid earlier this month. The results, expected within weeks, will determine whether Berlin needs to rethink its approach to nuclear.

The analysis is expected to point to particular risk in Bavaria, where the conservative government has long battled against both wind turbines and high-voltage lines that could bring green power from windswept northern states. The state also has little coal power.

While nuclear power contributes less than 6 percent to Germany’s power mix, for Bavaria, it’s double that: The Isar II plant near Munich generates about 12 percent of the state’s electricity. The region’s gas storage is also filled at below average.

That was enough to shift the stance of the Munich city government, where the Greens are the largest party.

“If the stress test … shows that Munich is threatened by a power supply bottleneck, a stretch-out operation of Isar II must not be taboo,” Green Deputy Mayor Katrin Habenschaden said. “As mayor, the security of supply for the people of Munich is my top priority.”

Party split

Many senior Greens are sending out mixed messages.

Foreign Minister Annalena Baerbock has both said that all options need to be considered in an emergency and that nuclear power wasn’t the answer to the current crisis. Climate and Economy Minister Robert Habeck has declined to rule out an extension while arguing that nuclear power wouldn’t save very much gas.

But there’s also pushback. Britta Haßelmann, parliamentary leader of the Greens, said the phaseout cannot be “called into question.” Environment Minister Steffi Lemke, responsible for nuclear safety, has also voiced opposition.

Although it’s mostly the older generation of Greens for whom marching with now-iconic buttons labeled Atomkraft? Nein danke (“Nuclear power? No thanks!”) formed their political awakening, even the Greens’ youth leadership has called the debate “dangerous.”

Some of the fiercest resistance is expected from Greens in Lower Saxony, which over decades saw some of the most intense protests against nuclear power. The state is heading for elections in the fall.

Germany's Foreign Minister Annalena Baerbock and Climate and Economy Robert Habeck are both from the Greens

Germany's Foreign Minister Annalena Baerbock and Climate and Economy Robert Habeck are both from the Greens

“Nuclear power is not the easy solution, it is a highly dangerous fake solution, even in the short term,” Julia Willie Hamburg, the Greens’ candidate for the Lower Saxony premiership, told local media.

Their base is similarly split: A recent survey found 61 percent of Germans in favor of keeping nuclear plants online, but 57 percent of Green supporters against.

Months, not years

The Greens have faced a similar dilemma before. The party was rooted in pacifism as much as in the anti-nuclear movement — and then it found itself in government during the Kosovo war in 1999.

An extraordinary party conference, in which Foreign Minister Joschka Fischer was pelted with red paint, ended with a vote in support of German participation in NATO’s Kosovo intervention. There was a small exodus of pacifist members, but the party survived. These days, the Greens are often at the forefront of demanding weapons for Ukraine.

The Lower Saxony Greens are expected to demand an ad-hoc party conference should the national leadership back a nuclear extension.

The Greens in Berlin, meanwhile, have tried to avoid a public falling out by suggesting a party line to take on the issue.

An internal email from the party headquarters to various branches, obtained by Die Welt, asked for questions on the nuclear issue to be answered “calmly.”

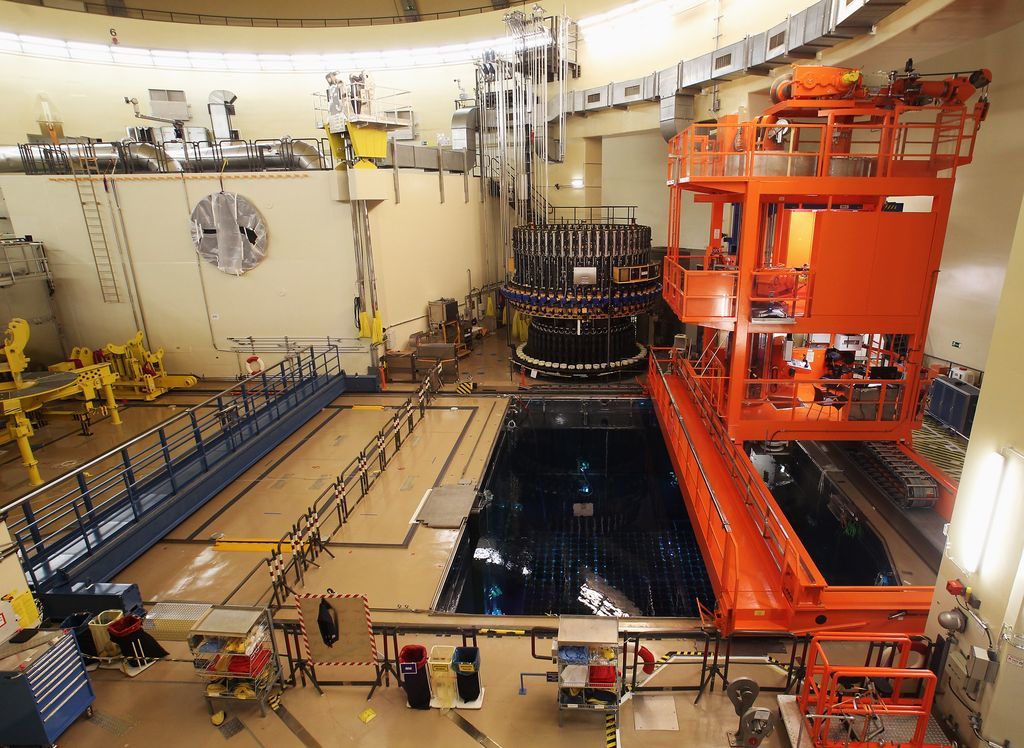

The Isar II plant near Munich generates about 12 percent of Bavaria's electricity

The Isar II plant near Munich generates about 12 percent of Bavaria's electricity

The email suggests the following line: “As soon as the results [of the grid stress test] are available, possible further measures will be discussed — as before — on the basis of the facts. We reject an extension of the operating term, i.e. the procurement of new fuel rods.”

The last line is where the compromise could lie.

While conservatives have called on the government to procure new nuclear fuel and liberals have suggested a new phaseout deadline of 2024, Greens who have softened their stance still reject a longer runtime.

Their focus is on stretching existing fuel supply, which doesn’t require new uranium rods.

Several experts have said this wouldn’t produce more electricity and just stretch power generation over a longer period — although the Munich Greens, for example, cite safety inspectors as saying that the Isar II plant could create an additional 5 terawatt-hours until August 2023 this way.

New rods would give several more years of power, significantly delaying the phaseout — which the Greens want to avoid — and also create additional nuclear waste.

It’s not quite “yes please” to nuclear power. But it would be a major shift away from “nein danke.”